BLOG

Life confronts us with challenges. And in times of crisis, like the recent earthquakes in Turkey and the war in Ukraine, these often seem overwhelming. It is natural for us to feel disoriented, with low mood, low energy and struggle to feel ok during the day and night. The nervous system has in-built resilience to experience these phases of tension, difficulty and suffering. Over the past several hundred million years, we’ve developed an incredibly sensitive and intelligent capacity to remain alive and engage in the world, despite all these difficulties. One heart quality, in particular present for mammals such as us, has made a big difference: compassion.

Compassion is the ability to identify suffering, understand it, feel into it as well as the motivation to alleviate it. Compassion, for me, has been among the most difficult heart-qualities to develop. In my meditation practice and in my life, I have been very strong and committed on goal-achievement, and the cultivation of equanimity (equality of mind) and joy. But compassion is an entirely different posture, a new relationship to the dark side of our lives and minds. It requires a lot of patience, a lot of self- and other-oriented empathy, a deep quality of listening the quivering of the heart.

Being vulnerable, open disclosing a sense of suffering is often perceived socially as being weak or inadequate. We are often faced with a willingness to help but feeling powerless. I remember working with a client at one point, they were faced with chronic pains in the body due to the many operations they suffered. They said they stopped talking about their pain because everyone around them did not have the capacity to hear how much pain she was going through, did not have the required compassion, and therefore held that burden to herself. She did not expect people to find solutions to her pain, just that they could make some space hear her, be understood and welcomed. Because this did not happen, she was holding a second load of suffering, on top of the physical pain: the pain of being misunderstood, the pain of disconnection, the pain of exclusion.

In meditation we can develop this internal compassion, this posture of deep listening and caring for our own grief, pains and suffering. We can learn to hold ourselves dearly, softly, as a loving caretake would hold their baby. In times of crisis, there is so much suffering within us and around us that compassion can make an enormous difference to how we hold ourselves and others. Not expecting change, not expecting ease, not expecting for the suffering to go away, but instead being willing to make space for it. And paradoxically, when we bring ourselves to welcome difficulty, it becomes lighter! Ease and deeper breathing can emerge, a sense of softness and a larger heartbeat can be felt. Evolutionarily, compassion is a very recent but extremely powerful process of integrating our shadows, our suffering and challenges.

Finally, there is a time to celebrate our efforts in the development of compassion. Recently I worked with some individuals who were holding spaces for victims of the Earthquake in Turkey, and they were acknowledging how much more able they were able to stay present in the face of extreme pain. They were really growing their compassion to a whole new level, and even though this was a real challenge and not easy, they were able to see these steps forward. Celebrating these little steps together made a huge difference: we were able to rest a little bit, breathe some more. We were able to joke and enjoy one another’s company, appreciate our time together. It gave us a break from focusing on what was painful, and allowed more ease to be felt in the space and our bodies. It also gave us strength to go deeper, and take further steps for the development of this compassion. We all need to feel strong sometimes, and celebrating our little successes and moments of ease and joy are essential for that.

May compassion be present in us, for the benefit of all beings.

We are offering a online meditation retreat on April 28 – 30, on the topic of “Meditation in Times of Crisis”. Apart of a registration fee of CHF 5,00 it’s completely donation based. Learn more about it and register here.

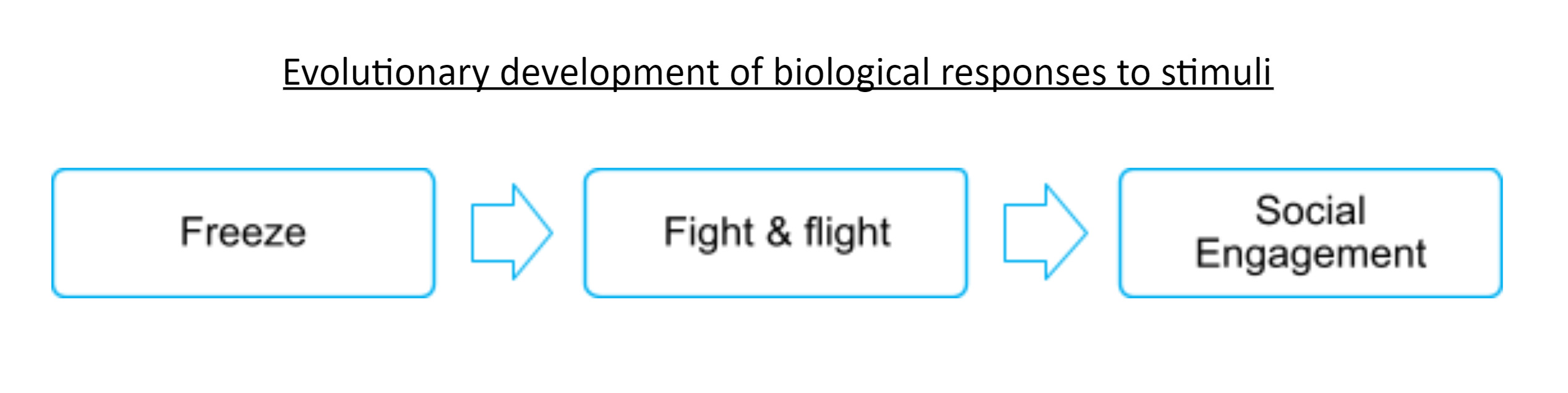

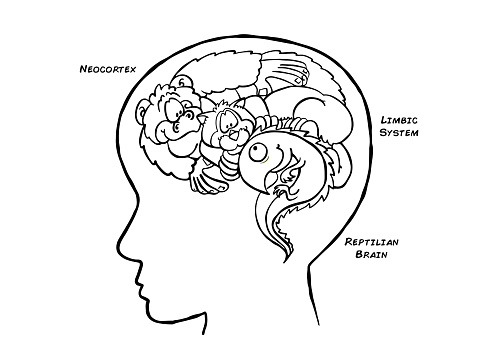

One of the main insights from evolutionary theory is that as it unfolds, life becomes more complex, more intelligent and more skilled. In fact, this increase in capacity is a necessary condition due to the process of natural selection: the survival of the fittest. One of the great developments in living beings over the course of evolution is the emergence of the nervous system: a central intelligence which helps organize and coordinate resources, energy usage and interactions with the environment. Hundreds of millions of years ago, complex life increased its chances of survival by going into a freeze state: like the possum who fakes being dead in order to be able to trick the fox that he’s already dead and not worth eating. Later, we learned to flight and fight, further enabling us to remain alive in the face of threats. The fact that these nervous system responses evolved over time is very significant because it means that they are increasingly intelligent and complex. It also means our nervous system operates hierarchically: when faced with a threat, we will first evaluate the possibility of fight, then flight, then freeze. These principles have big implications for the meaning of meditation and how to practice it! I’ll share a few insights here from my own practice.

First off, since I was a child, whenever I was confronted by something difficult I’ve had the tendency to go into freeze as my go-to threat response. And it served me well! I was able not to get into much of harm’s way and have a mostly happy childhood. However, when I started meditation, because I couldn’t tell the signals of freeze, often when I came across a difficulty I would leap into freeze right away. Due to my lack of awareness of the nervous system and how to regulate it – I didn’t even know about this state of freeze – I sometimes would do a very unhelpful thing: (pathologically) strengthen that pattern of going into freeze.

These trends did not help my live a more meaningful and regulated life, on the contrary. Meditation started to have some perverse effects in the way I was interacting in relationships and my engagement with the world. For example, whenever I was experiencing difficult emotions with other people, I would favour states of ‘calm and equanimity,’ considering these to be higher states than states of fight or flight. Because the nervous system operates hierarchically, if we experience freeze, this means we’ve exhausted our ability to fight and flee the environment, and use our last resort solution to survive. In a way freeze is a higher state, but it also impacts the system more powerfully and destructively if accessed to often! So over time, I learned the importance of experiencing fear for instance (which would often get me in a state of flight), or frustration/anger (which would often get me in a state of fight).

That way, I’ve been learning to experience a broader range of emotions and states, more adaptively. And that word to adapt is really the key one: connecting to the experience that we are facing with the appropriate/adaptive response. There is a growing consensus that the essential skill of regulation is cognitive flexibility, which also means adaptive responsiveness. So instead of going into a disconnected, distancing and ‘calm’ state of freeze whenever I remember being criticized sharply and I’d been upset about it, I’ve been encouraging myself to explore emotions of anger, resentment, sadness, etc. Paradoxically, it now consumes for me less energy to feel a strong emotion like anger than to go into a state of ‘calm’ because once it’s felt, then the sympathetic arousal that was ignited through the criticism is discharged (rather than being stuck in the body as it does when going straight into freeze).

The key point, from a nervous system perspective on meditation, is that all emotions are actually essential to be experienced. Embodying the full range of emotions in meditation helps build a more resilient nervous system that is less dysregulated and has less energy stuck in the body system. Come and join us at the next Dharma Gathering to practice these skills!

What is the purpose of meditation? Shapiro (1) studied that question empirically with meditators in California, and found that participants’ answers fitted into at least one of three categories:

- Self-regulation: achieving a sense of wellbeing

- Self-exploration: knowing oneself

- Self-actualization: embodying and developing the fullness of one’s character

A closer look at the early Buddhist teachings (the Pali canon) offers a similar goal for meditation, albeit in different terms: “freedom from stress.” While this may seem at first that being free from distress only relates to being regulated (the first category above), both knowing oneself and developing qualities are also essential to this task. Looking at my own experience, I went through a deep depression in my early twenties because I could not understand my place and purpose in life. I had just separated from my girlfriend, with whom I thought I would be “happy ever after,” and did not see a future for myself in the business and economics degree I was completing at university. I had all the ingredients to feel good: sufficient resources to cater for my basic needs (and much more), plenty of friends and a very active social life, a loving family, great physical health, and a bright future ahead in the line of my professional career. Yet, I fell into depression.

My mental health was affected not just by all the factors named above, but also by a need for a deeply satisfying sense-making framework of who I was and what my place was in the world. That was missing, and it felt like I was living an increasingly darker nightmare as my desperation increased by the day. That’s when I decided to go to Thailand and start an period of meditation in Buddhist monasteries.

I practiced intensive meditation in Thailand for about six months, and a lot happened. I’ll explain more details about that in another blog post, but what I’d like to share now is that my study and practice of the early Buddhist teachings offered a conceptual framework and a systemic set of teachings to relate to my experience that was inspiring and meaningful. Finally, I could start to understand more clearly, and validate a growing intuition, that there was more to me, who I was, the world I was living in and how I experienced others than the story I had been told of a Newtonian, objectified, separate and materialistic existence.

At the core of it, my main insights centered around

- the need to cultivate a perceptual capacity in order to have more moments of harmony inside myself and with others and the world

- the importance of working towards a transcendent goal (nirvana) because the quality of every one of my present moment states are directly impacted by it

I could quite easily fit both of these goals into the latter two categories in Shapiro’s study: understanding myself, how I perceive myself as well as the development of new ways of being amount to self-exploration and self-actualization. What was missing though? Self-regulation! I was very intent of understanding, expanding and transcending myself, but brought no importance to being grounded and feeling good. Instead, I practiced a lot of (sometimes extreme) asceticism, in order to intensify exploratory and transcendental experiences, which eventually got me into a lot of trouble, and why I turned very seriously to a nervous-system centered approach to meditation. What is that and how does it work? That’ll be the topic of next month’s blog post.

(1) Shapiro, D. H. (1992). A preliminary study of long term meditators: Goals, effects, religious orientation, cognitions. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 24(1), 23-39.

*Systemics: the need to include my place in society, and how society affects me

“What you frequently ponder upon, that becomes the inclination of your mind”

– Buddha (1)

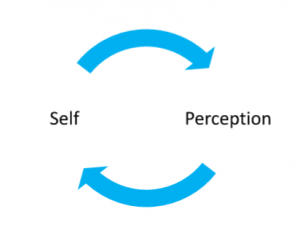

I am my perception. As I walk down the forest close to my home in the autumn, I smell the pine trees, I see the wide variation of colours as all other trees lose their leaves, and hear some birds singing softly. I am momentarily mesmerized by how beautiful and enjoyable it is to be surrounded by all this life and vibrancy. And from that, there is a sense of greatness of life, of oneness and a deeply harmonized sense of who I am and my place in the cosmos.

The thing is, as I am Swiss, I have grown up going to the mountains and forests very often, yet never got to perceive nature and myself in this way before. Undoubtedly this comes from a prolonged meditation practice and deepening appreciation of nature, both of which help to beautify a relationship to myself. Training in perception, as we do in meditation with qualities such as mindfulness, love, compassion, joy, equanimity and somatic sensitivity have influenced how I perceive myself, and vice-versa.

I have often been taught that meditation is about “being the present moment with what is.” However, though acceptance is obviously a key component of meditation, as I follow my perceptual development over these last 15 years of practice, I see other patterns emerging: more beauty, more belonging, more calm and more joy for example. And so why not intentionally develop these outcomes

This is something I have been growing into these past few years: intentionally orienting my mind towards ‘positive’ qualities such as beauty, space, pleasure, contentment and gratitude. I have found that there is most often something, even the tiniest little thing, in my perceptual experience that involves some kind of positive quality, and with a sustained attention towards that, it grows (2). At this point in my practice, I spend most of my time co-creating my experience along with spontaneous impulses coming from my nervous system, the external environment as well as imaginal drives. This last dynamic of imagination, seems to be most attractive to me now, where I allo.w my mind to create shapes, forms and colours that seem to be most harmonizing to my experience (in my imaginal repertoire). One of the indicators for this harmonizing quality that I intuit around is the somatic resonance of these imaginal impulses. For example, in my meditation this morning, I felt some narrowing perceptions on my body which got me feeling more anxious, and spontaneously I would reach out for more space and orientation outside my body, I literally created space and broadened the size of my energetic and perceptual field. It then got to the point where it felt too large and anxiety started creeping in again, with agitating waves and a feeling of fear, so I relaxed by coming back into the body softly, feeling the earth under me and gently sensations of ease and pleasure also available. This creative-imaginal movement from the creation of space, back to orienting towards palpable somatics of pleasure and groundedgrowness is an example of the intuitive skill I call somatic imaginal: allowing the nervous system to feel soothed, brightened and dynamized (“somatic”) by producing whatever impulses coming to mind spontaneous (“imaginal”).

Next time you sit in meditation, it may be worth experimenting to find out: “what images (forms, colours, sounds, voices, dimensions) help to soften and dynamize my somatic experience in this moment?”

Come and join our next Dharma Gathering on December 4th to further embody your imaginal capacity!

(1) Two Kinds of Thought, Majjhima Nikāya 19

(2) See Broaden-and-Build theory from Barbara Fredrickson

“The climate crisis is a crisis of view”

– Rob Burbea (1)

Our moment-to-moment experience is influenced by many factors, including the environment we are in. By the environment, I mean the immediate surroundings as well as the larger ecological and societal context we inhabit. I remember a time on silent retreat when it was cold because of winter, and I practised meditation for long periods indoors. It was enjoyable to feel the warmth of the fire, listen to the crackling wood and see its embers. It felt so alive, so vibrant, such a presence despite the loneliness in my hermitage. I thank the gods and goddesses of nature for being such a support during difficult times.

We evolved intimately with nature, and whether we feel our immediate environment matters to our sense of belonging and embodiment in each moment. Nowadays we urban people spend so much time on our tech equipment (phones, computers, cars), that feeling intimate with nature is not a given. There has recently even emerged a new mental health diagnosis of Nature Deficit Disorder (2). Our modern industrial societies, influenced by secular humanistic and Cartesian body-as-object-of-mind, have conditioned a challenging dynamic to our relationship with the environment and nature.

Sacredness can be felt in many varieties and infinite ways. What do we hold sacred in life? Is nature included in this sacredness? It is worth contemplating our relationship with nature and explore ways in which we can enrich our meaningfulness and sense of belonging on this planet. Let’s take a moment and feel Earth’s embrace – the pull of gravity on our bodies and hearts – and allow that to ground us and enable a letting go right now.

How is it to rest on Earth’s force and holding?

Let’s feel into the breath…

How things look outside as we allow this?

Our minds are often pulled in many directions, and yet there is also this opportunity to enjoy Earth’s embrace. Perhaps there is a way in which the pull of gravity can be felt as Earth’s love for our bodies and hearts.

We are right now at a key moment in our human and history of evolutionary life altogether. The climate catastrophe is starting to be widely felt in its impacts on our societies, at the edge of civilizational collapse (3) (notwithstanding the extinction period we have just entered). Is life around us and as the species itself a part of our sacredness? Let us take another moment and feel into the goodness and liveliness of having other beings around us. How is it to feel the birdsong in the morning, walk with dogs, caress cats, ride horses, or other animals resonating in our imaginal space?

Let’s bring to mind a moment when we felt an animal’s love.

Sensing into that experience, sensations, breath.

Taking time to enjoy and appreciate.

As we feel the nourishment from the life around us, and our dependencies on many many other species, perhaps our hearts open. And from this open heart, we can feel a deeper belonging with others, on this planet, together. I encourage all of us to include life and the Earth itself to be included as imaginal forces in our meditations, uplifting our hearts and grounding our bodies. From this love of nature and a felt-sense understanding of ecology, our activism, belonging, groundedness and contemplative practices can enable new ways of being into this world. This sacred world, with its myriad beings and mysterious ways, is worth protecting.

Come and join our next Dharma Gathering or Retreat to further embody Earth’s embrace and love for life!

(1) « An ecology of Love » Dharma talk by Rob Burbea, 21.12.2015: https://dharmaseed.org/talks/32201/

(2) “Ming” Kuo, F. E. (2013). Nature-deficit disorder: evidence, dosage, and treatment. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 5(2), 172-186.

(3) Degroot, D., Anchukaitis, K., Bauch, M., Burnham, J., Carnegy, F., Cui, J., … & Zappia, N. (2021). Towards a rigorous understanding of societal responses to climate change. Nature, 591(7851), 539-550.

“We inter-are”

– Thich Nhat Hanh (1)

With mainstream values of individualism, we will often tend to consider ourselves as separate from others, nature and the world. However, a new research paradigm in somatic neuroscience emerging called “radical embodiment” (2-3) ), shows that the shape of our sense of self differs based on our social context. This has profound consequences for our meditation!

When we feel safe with others, we broaden the edges of our self to include others and when we feel threatened, we tend to close up and narrow our self-construct. And this relational phenomenon has direct impacts on how we experience our bodies and can self-regulate. Because we have a wider sense of self with good friends, actions require less effort than if we were alone or with difficult company. Actions are less “bioenergetically costly” (4) because we assume that others are a part of our body and therefore budget our efforts based on a larger pool of resources. Others literally become resources for us. This means that the people we have around us really affect how we experience our bodies, our immune functions (5) and many other foundational physiological process for basic health.

Moreover, the presence of other people also affect how we relate to ourselves psychologically and attentionally (6) . I have been experimenting with groups of friends and in teaching retreats how paying particular attention to others, and meditating together with short phrases of loving-kindness and noting of one’s present-moment experience offered a different way of connecting to one’ own internal experience. And I totally love it!

I have spent many years in retreat, in silence, alone and certainly benefited in immensely powerful, unique and life-transforming ways from this. I do think that developing this form of self-reliance, calm and depth of commitment to any practice opens to high levels of devotion, insight and transcendent opportunities. AND, there is so much that can also be experienced and explored in relationship and with a deeply trusting relational container.

In NeuroSystemics then, we pay attention to the interaction between relationships and our quality of presence. We learn to practice and nourish a co-created safe space so that we can all go deeper inside and free ourselves from suffering. Being in relationship with others takes some work, and at school we don’t learn basic listening, emotional expression or conflict resolution skills so these do not come easy. However, as we learn to engage with others a participate in the design of a skillful social space, we can all go deeper.

Come and join our next Dharma Gathering or Retreat to further embody this quality!

(1) “Call me by My True Names – The Collected Poems of Thich Nhat Hanh”, Parallax Press, 2005

(2) Raja, V. (2021). Resonance and radical embodiment. Synthese, 199(1), 113-141.

(3) Beckes, L., IJzerman, H., & Tops, M. (2015). Toward a radically embodied neuroscience of attachment and relationships. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 9, 266.

(4)Coan, J. A., & Sbarra, D. A. (2015). Social baseline theory: The social regulation of risk and effort. Current opinion in psychology, 1, 87-91.

(5) Dos Santos, R. M. (2020). Isolation, social stress, low socioeconomic status and its relationship to immune response in Covid-19 pandemic context. Brain, behavior, & immunity-health, 7, 100103.

(6) Sieber, A. (2015). Hanh’s concept of being peace: The order of interbeing. International Journal of Religion and Spirituality in Society, 5(1).

🌊 Taking care of your mindsoulheartbody after a retreat 🌺

Aka help, I was just in meditative/community bliss for a week and my heart chakra got big as a tree and now I’m on a street in Brooklyn and my mom just yelled at me on the phone and I almost got run over by a bike

So you were in a retreat, a workshop, a community, an experience. Maybe your heart feels wide open. Maybe you’re now wrestling with many inner questions. Maybe not much has changed. Heightened experiences can be powerful and bring us new perspectives, new friends, new ambitions. What’s also interesting about them is that the transition back to our daily life can be tricky. It can be helpful to have a bit of a roadmap.

Indeed, besides all the delicious feelings of warm connection and hope that can stay with us long after we’re home, some of these may also show up:

- Feeling disconnected from your “normal” life, from loved ones and friends

- Feeling incredibly sensitive, as if your top layer of skin is gone/your usual protections aren’t there

- Feeling moments of big high that transition into big lows

- Feeling alone and abandoned, craving the community or group you just left

- Feeling ecstatic all the time

- Feeling physically ill

- Feeling an urge to convert everyone around you to what you’ve just experienced

- Feeling lost

- Feeling hopeless about the fate of the world

- Feeling dissociated, “up in the clouds” and ungrounded

- Not knowing how to integrate what you’ve learned and experienced into your daily life

- Despair when the special, pleasant feeling of the retreat starts to dissipate

Know you are not alone. These experiences are shared by many, many retreat participants. And it makes sense! A central notion in somatic therapy is the fact that expansion is usually followed by contraction: when we have an experience that opens and challenges us in a way we’re not used to, our system then contracts to try and find stability again. Most of the uncomfortable stuff in that list? Contraction. This is normal and natural, and if we let ourselves slowly and gently integrate the expansion, our everyday state can become a little more expanded than it was before. That’s how we progressively gain more and more capacity over time to be with life in all of its richness.

How do we integrate slowly and gently, you may ask?

First, let’s take a breath.

🌬️

Now let’s get some inspiration from the deep blue sea.

Decompression stops

Deep sea divers are just like you. They swim down to spend time in the depths, where they experience a magical, disorienting swirling of time and experience, and get to see things they could never find close to the surface.

Divers also know that coming back from the depths requires a process in order to return safely. Put your science hat on for a second: At great depths, the body of the diver quickly becomes saturated with nitrogen. When they start to ascend towards the surface, the pressure of the surrounding water decreases and the nitrogen accumulated during the dive returns to their blood in the form of microbubbles. If a diver swims up too quickly, the gas expands so fast that the body cannot eliminate it safely, and the diver develops decompression sickness. The consequences can be serious and even fatal. Therefore, divers make a series of decompression stops to allow their bodies to acclimate to the decreased pressure. At each decompression stop, the diver breathes normally, allowing the dissolved gas to be expressed.

You can see your own process coming out of a retreat as a journey of decompression stops.

The length and rhythm of this journey and the number of stops are entirely your own, and differ for each of us according to our needs. The more gentle and conscious the process is, the more likely it is you’ll be able to digest everything you experienced.

🌬️

Hey you. Let’s take another breath together. Nice.

🌬️

Here are some ideas of what this landing journey could look like.

Soft landings

The point of decompression stops is for you to experience a soft landing. The idea is to avoid an abrupt transition between retreat life and “real” life, to answer the following question: what would make this landing back into your life softer? Another major notion in trauma and somatic therapy is that our systems can default to speed and “moving on to the next thing” whenever we feel emotional stress. It’s a great skill to acquire to live change processes gently and moment by moment.

A key question you might want to ask yourself before reading further is: in my life so far, what has helped me deal with transitions? What helps me feel safe in the midst of change? Start there.

Examples of soft landings

As the experience is wrapping up

Endings are important. The end of retreats and group experiences can go by in a rush when emotions are high and we don’t want the experience to stop. Experiment with slowing the ending process down. What does that bring up?

On the journey home

If your retreat was residential, is someone in your group open to traveling back together part or all of the way?

Rather than rushing home, can you take a second to see what connections might come up along the way? It can feel surprisingly nourishing to talk to a cashier in the airport about the weather rather than rushing to sit at the gate. And if you’re feeling like you need 0 people time and to minimize contact, of course then that is the thing to follow.

Once you’re home/you’ve reached your next destination

What feels grounding when you’re home? Do you have a favorite meal? A neighbour you like to check in with? Your system will probably want to reconnect with a little familiarity. Let it. I promise you won’t lose all the newness you just got.

The next little while will probably involve reconnecting with the day to day while staying connected to the experience you just had. To support the latter, the following might help:

🌸Did you get close with someone in your group? Could you agree to daily brief check-ins for the next week or so?

🌸Does anyone in your group feel open to having weekly check-in Zoom meetings for a few weeks following the end of your retreat? Often many people are interested, because they need integration just like you!

🌸Does anyone in your group want to create a Whatsapp group or email chain?

If you’re going to stay in touch digitally with new friends and/or lovers, it can be very helpful to discuss how you each approach digital communication. We tend to have varying expectations and approaches to using our phones. Some of us like to feel very connected and use our phones as extensions of our every day communication-self. Others don’t love being on their phone, and don’t use it as a tool for deep or emotional communication. Whatever way you function is fine. Get the lay of the land and be clear about your personal approach so that your feelings don’t get unnecessarily hurt.

After a retreat I participated in recently, the other participants and I decided to share a list of the specific actions we wanted to integrate into our lives after the retreats. We made a document with the list and we agreed I would send the list to everyone again in 1 year exactly to see how we did.

Can you have regular moments of integration with one friend or therapist over the coming weeks? (If people are not your thing, a favorite nature spot, plant or animal works wonders too.) Make sure you allow yourself to set all the boundaries and requests you need around such a moment. If you need your friend to sit there and listen without giving feedback or commenting, make that clear. See if that works for them. Consistency and continuity can be very helpful here, so an idea can be to see if one friend feels open to being your appointed integration person for those few weeks.

A little recommendation: Exercise discernment about who you share your experience with. You may feel like telling everyone about the beauty you just experienced, you may feel like you now have answers to friends or family members’ problems, you may feel like you’re now ready to heal things with your complicated parent. It may well be the case! It may also be worth first really checking in with yourself and grounding your experience. Trust that whatever you learned and can share will not disappear as the weeks go on.

When we return from such an experience, we are often very open and a little fragile because of that openness. If we share with others who have not been in the same safe, heart-open space, we may have to deal with some intense responses we don’t have the capacity to handle…

Overall, as much as you can, let yourself go slowly and touch base with whatever and whoever in your life feels trustworthy, safe and resourcing.

🌬️

Take a second. Let’s breathe again. You’re doing great.

🌬️

Grounding and integration

A frustration that can come up after a retreat is not knowing how to translate everything you felt and learned into action or change in your life. Here again, slow down. It’s normal for this process to take time.

Anything that helps move your ideas, emotions and impressions into the physical realm can help:

🌱Take care of that mindsoulbody! Rest! Drink water! Rest more! Go on a walk! Roll around in the grass! Dance awkwardly! Eat kitchari or Nutella, depending on your deep need! Shake shake shake! Or lie there like a carp! Light candles! It’s all good. I know if I don’t do some gentle movement or walking after a retreat, I get all locked up. Emotional experiences are deep body experiences, and they can summon immense amounts of physical energy.

🌱Experiences that open us up can also make us lose our sense of where we end and begin, literally and physically. Give yourself containment: Hug yourself, asks for hugs and/or ask someone safe to lie on top of your back while you lie down on your belly (trust me try it), walk barefoot, wrap a tree branch around you.

🌱Journaling

Some examples of journaling prompts

- What are the three main things this experience has brought me?

- What parts of myself did this experience help me connect with? What emotions? What parts of my body? What might these parts want to tell me if I give them the space?

- What do I want more of in my life? What do I want less of?

- What actions do I want to take in my life to honor this experience?

Are there concrete projects that this experience has inspired me to launch into? What would I need to get those in motion?

🌱Drawing

Some examples of integration drawings below

(Having someone read your stuff or look at your art can feel extra grounding, if you are comfortable)

🌱Chop wood, carry water. Normal life stuff can be very grounding. Laundry, dishes, watering your plants, cooking, cleaning, taking care of the kids. Getting some space from intense experiences and letting your attention go elsewhere can be very helpful to integrate.

🌱Find simple practices in the everyday that connect you back to deep feelings, to grace. When I spent some time in Plum Village, a Buddhist community, a bell rang every hour or so. We were told very clearly that every time the bell rang, we were to stop what we were doing immediately and take three breaths. I don’t have a bell, but that habit has now become a part of my daily life. I used to set random timers on my phone, but now I just do it naturally whenever my mindbody needs it.

Sangha, baby

We’re all different creatures with different social needs, but the common thread to every retreat experience I’ve ever had has been the emphasis on community. It can feel incredibly hard to stay consistently connected to anything soft and deep in the insanity of daily life without the support, example and encouragement of like-minded others. The great thing about many retreats is they come in with a built-in community. Let those connections happen, foster them, let the groupmind bring you its online or live support after the retreat is over. And don’t be afraid to seek out more community where you live. Buddhist Teacher Jack Kornfield wrote an entire book about the process of coming back to daily life after heightened experiences, with the delicious title After the Ecstasy, the Laundry. Thanks Jack. He shares a meditation teacher’s experience that reflects the importance of our people to help us through integration:

After five years of retreat and some extraordinary meditation experiences, I went back to live in Seattle. My perspective was changed, truly different from those around me. At first, the city seemed exciting, but also somewhat frantic. I didn’t know how to put the inner and outer worlds together. Then I grew increasingly overwhelmed on my own. I felt lost and a little crazy. I really needed spiritual friends. When I found some they helped me through the difficult years. Remember this when times are tough. It’s the most important thing I can say – don’t forget spiritual friendship.

🌬️

One more breath? Yeah let’s do it.

🌬️

The process is rarely linear

Based on what’s been said so far, you might feel like your process coming out of a retreat should look like a straight line. Integration actually more often looks like a process of ebbs and flows. Once you’re home, you might completely forget about everything that just happened on your retreat while you get back into your daily flow, and suddenly find it all flooding back in a moment when you’re less busy. Or you might be incredibly emotional for weeks after your return, and fight to get some grounding back in. All of it is OK.

Some common fears that can creep in as life moves on after a retreat:

It felt so powerful, but now I’m home nothing’s changed. Did it even matter?

How could I possibly find that feeling again?

Everyone else on the retreat seemed to be so affected by it but I don’t feel like I was. Is something wrong with me?

You might have heard your therapist encourage you to trust the process. They’re right. Trust the process. Trust that when people in a closing circle say the experience was „earth-shattering/life-changing/that they feel more love than they‘ve ever felt in their life“ and you‘re sitting there like „umm, I don‘t feel that“, maybe they do feel that, and maybe they‘re bullshitting, and mostly it doesn‘t matter. You‘ve got your process, and you get to trust it.

Trust that change doesn’t have to be huge and major and immediate to matter. Trust that whatever you personally connected with through that experience is enough and is what matters. Trust that others probably left with something different, and that is also good. Trust that what you really learned can take some time to reveal itself. The lessons will seem to disappear and then come back again, so that years later you realise how much you’ve gradually changed.

The kirtan singer Krishna Das has a great metaphor for change, that it’s like being on a train moving forwards on a journey. You can walk up and down the train, sometimes moving to the very last carriages, which can feel like you’re going backwards. But the train itself is always moving forwards. Remember that.

😘

by Pauline Baudon

“Wise Anger”

“Anybody can become angry – that is easy, but to be angry with the right person and to the right degree and at the right time and for the right purpose, and in the right way – that is not within everybody’s power and is not easy.” – Aristotle

Anger is a very challenging emotion most of the time for most people. Do you ever get angry? Do take a moment a notice when anger comes up for you (I would be very surprised and curious if it didn’t).

When I was trained as a Buddhist monk in Thailand, anger was regarded as one of those emotions that I should have aspired to be free from. It was unskillful to be angry, since it (supposedly) always led to bad outcomes. My instructions was to note it in my mind “angry, angry, angry” until it passed. Using meditative skills in this way certainly helped me to gain more control over the anger, and find other ways to be with it than just to completely inhibit myself around it (other people also act it out on other people, but I was never able to do so).

For a few years, this worked! I felt more at peace and thought I had resolved my anger issues. However, when I abandoned my vow of celibacy and got into a romantic relationship, anger came up again regularly, and that meditative trick did not work anymore. That’s when I started studying conflict resolution and came across research from Gottman’s lab in the USA. Gottman conducted decades of research to identify what help couples be happy, and I found one big surprise: expressing anger was often helpful! How does this work?

Anger as boundary

The psychologist Young-Eisendrath wrote that “anger, when used as a boundary setting expression of frustration, is weed prevention.” The rationale here is that when we feel angry about something, it shows that we have a boundary which has been crossed, a need which is not met. Anger therefore arises as a signal that something important is happening for us here: a heart-seed is in endangered by a weed. From a meditation point of view, there’s ways we can connect into our experience to (ii) reduce the intensity of the somatic and emotional reaction (like with the noting practice above), and also (ii) explore the cognitive aspects of the needs/seeds which are involved. This second part will most probably involve other emotions like fear, sadness and loneliness.

Anger & timing

Many of us tend to bypass difficult emotions, distract ourselves or repress them in some way – and I would argue even the Buddha did. This can be helpful since we need a great amount of resourcefulness and resilience in order to be able to cope with the emotions (which we often do not have), or there may be other priorities to attend to when anger arises (i.e. getting on a departing train rather than arguing!).

From a nervous system perspective we can learn to assess whether we are sufficiently:

- oriented: we are aware of ourselves in the physical environment in which we’re in

- social engaged: we can bring any of the heart qualities of the brahma viharas (see previous blog) such as love, compassion, joy and equanimity to our experience at any moment

If we ourselves lose our orientation and social engagement capacity for a certain period of time during our experience of anger, then we’re probably not able to follow Aristotle “at the right time” instruction. Then, since we’ll be expressing anger with another person, it’s also important to find out how our anger is landing with them: “how is it for you to hear me out as I am angry right now?” Do they have the orientation and social engagement capacity to listen and discuss this in this moment?

Conclusion

Anger is most often a difficult emotion, and the intensity with which we feel it signals a need to take seriously. Meditation training can help to regulate the somatic and emotional intensity often associated with anger, and inquiry practice can help to better understand the need behind it. Is it ever possible to get angry in the way Aristotle proposes? Come and join our next Dharma Gathering or Retreat to develop all these skills!

“Cultivating Wisdom”

“Where do you go for wisdom?”– John Vervaeke

When you were a child, what did you want to grow up as? I remember that my big dream was to be so rich as to have a safe full of gold coins and swim in it everyday just as Uncle Scrooge would do. I was attracted to money, having lots of it, and the main aspiration behind that was to be free from worry and being content. As I finished my bachelor’s degree in business administration, studying finance, economics and management, I got disillusioned with the prospect of making money as an end in itself. I remember clearly one moment in a Human Resource Management class where I taught as a teaching assistant where treating humans merely as resources for an organizational goal felt so diminishing, putting aside essential life experiences like emotions and relational qualities. This contributed to my first depressive episode which later led me to go and ordain as a monk in Thailand to meditate and grow wisdom. That’s when things started to shift for me in a significant way to live more meaningfully.

What is wisdom?

I propose a broad definition of wisdom with Greek and Buddhist philosophical traditions in mind: wisdom is the embodied capacity to live a meaningful and joyful life. In Buddhism, there are 3 ways to develop wisdom:

-

- Information processing (suttamayapānna): information we can get from anywhere

- Reflection & deliberation (cintāmayapānna): forming one’s own perspectives by thinking about things and discussing them with others

- Intuition (bhāvanāmayapāñña): experiential understanding which involves a direct knowing

We can understand these three forms of wisdom as being more general and wide-ranging (information), to more specific and personal within ourselves and the people around us (Reflection and deliberation), to even more focused in terms of the immediate contact with experience and the present moment (intuition). Wisdom therefore involves all three of these perspective-seeking skills, and meditation focuses specifically on the 3rd form: intuition development. Experiencing within one’s own mind and body a certain quality

At NeuroSystemics, we encourage all 3 forms of wisdom: broadly we could say our trainings (such as the 3-year CARE Trainings) offer information/education with embodied experience, our Resiliency Circles (group process sessions) offer spaces for deep discussions and our Dharma activities offer opportunities to practice directly with our moment-to-moment experience in meditations and retreats.

Where do you go for wisdom?

We can meet friends at work, parties and activities; we can receive education at school and university; we can earn money by working hard and being committed to our goal; but where do we go to develop wisdom? In our western societies, it is not easy to identify popular wise people. A look at magazines, newspapers and social media will mostly point to stars linked with the entertainment industry or politics. But are they wise people?

Here are a few spaces for wisdom:

- A community of practice where you can feel safe enough to be yourself freely

- Your heart, which means taking times to gently connect inside and feel what is alive and feels meaningful

- Nature and the environment which holds tremendous evolutionary wisdom

- Animals, who’s nervous systems are often quite regulated since they have maintained their mechanisms for trauma release (often unlike humans)

- Where else will you go for wisdom?

Wisdom is not an optional skill, it’s an essential skill to develop in order to live a meaningful and joyful life. Come and join our next Dharma Gathering or Retreat to further embody this quality!

Compassion & Trauma

“Compassion is an essential evolutionary skill.”

– Prof. Stephen Porges

As humans, we are a social species. This means we are socially skilled to cohere and harmonize with others. One of the most essential skills we’ve developed is compassion. Compassion is defined scientifically as an other-centered “motivation state, characterized by feelings of warmth, love, and concern for the other as well as the desire to help and promote the other’s welfare.” (see footnote 1) Over the course of evolution, we have grown not just to express compassion to others in our tribes, but also to ourselves, psychologically. In the Buddhist tradition, compassion is understood as an infinite and divine abiding in one’s mind and heart to alleviate suffering. More recently in the West, compassion for oneself has emerged both in laboratory research and as mainstream practices. In this blog we will briefly explore the role and benefit of compassion practice in relation to trauma.

Trauma

Our metabolism has natural capacities to regulate itself: think of the homeostatic function of temperature which is constantly keeping our bodies at a range of about 36-37 degrees centigrade. A traumatic event or phase in our life would impact our system’s natural regulatory abilities to restore, regenerate and heal itself. Therefore, trauma can be understood as an experience that results in severely dysregulating the autonomic nervous system.

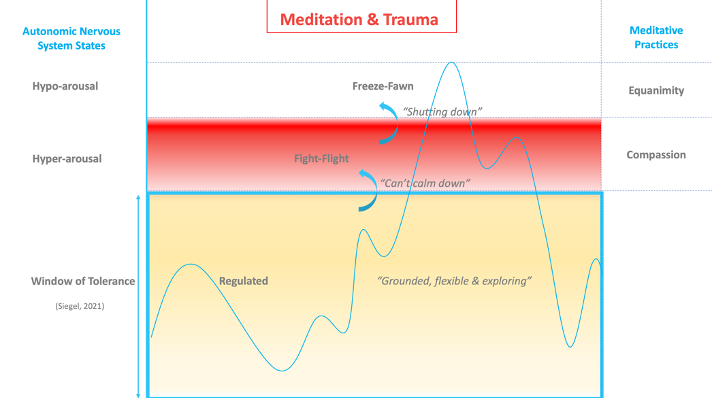

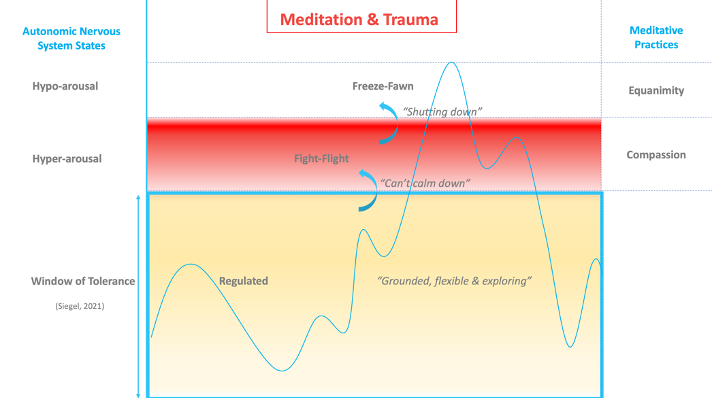

To describe this metabolic frequency Prof. Dan Siegel uses the term of a window of tolerance (where we feel “grounded flexible & exploring”, see figure 1). When we face a challenge, depending on our resources (both inner and outer), our system will respond resiliently (and remain within the window of tolerance), or by being overly pressured (“can’t calm down”), thus going into fight-or-flight. When our system is completely overwhelmed and gives up (“shutting down”), which is when trauma occurs, it goes into a freeze-fawn response.

Figure 1. From tolerance to trauma. Source: NeuroSystemics Dharma.

Compassion for Trauma

Compassion is a mental-emotional ability to help ourselves and others in the face of suffering. Fight-Flight are states which hold great measures of affect, and compassion will very often be helpful then. Freeze-fawn states, however, are characterized as having very little affect, a limited sense of the body and more neutrality. This means responding with a very compassionate attitude to a state of freeze-fawn (whether our own of another person) may be misattuned. It will more often be of greater help to invite a sense of equanimity (equality of mind, peaceful neutrality, see figure 2) to these traumatic states, and keep compassion when affect comes back online (which it will, as the freeze-fawn states becomes less intense). (see footnote 2)

Figure 2. Compassion & equanimity for trauma healing. Source: NeuroSystemics Dharma.

Compassion is therefore a powerful buffer before and after traumatic responses to difficult life events. By developing equanimity, which is a peaceful neutral presence, one can open up to one’s own or others’ freeze-fawn states and allow them to be more regulated and integrated. (see footnote 3)

Conclusion

The bottom line here is that as we navigate our internal landscape of our body, our heart and our mind, we will come across a whole range of states, both joyful and more difficult, and even traumatic. This is perfectly natural. And it is therefore essential to equip ourselves with a range of attitude and practices (i.e. equanimity and compassion) to best integrate the different states we come to experience. Come and join our next Dharma Gathering or Retreat to develop all these skills at www.neurosystemics.org/dharma.

Footnotes

1 – Leiberg, S., Klimecki, O., & Singer, T. (2011). Short-term compassion training increases prosocial behavior in a newly developed prosocial game. PloS one, 6(3), e17798.

2 – Weber, J. (2017). Mindfulness is not enough: Why equanimity holds the key to compassion. Mindfulness & Compassion. Mindfulness & Compassion 2(2), 149-158.

3 – For a review of compassion for traumatic treatment, see Winders, S. J., Murphy, O., Looney, K., & O’Reilly, G. (2020). Self‐compassion, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 27(3), 300-329.

NeuroSystemics Gatherings

I am because we are.

– From the Ubuntu tradition

Too many approaches in meditation are overly self-serving and excessively navel-gazing, placing one’s individual self at the center of both one’s suffering and liberation. This solipsistic tendency is a rampant consequence of over 200 years of post-Euroamerican Enlightenment: “cogito ergo sum – I think therefore I am” said Descartes. This needs to be adapted according to the latest social and affective neuroscience.

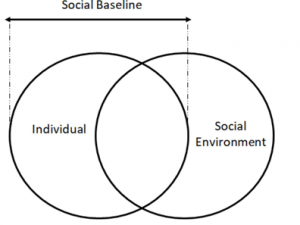

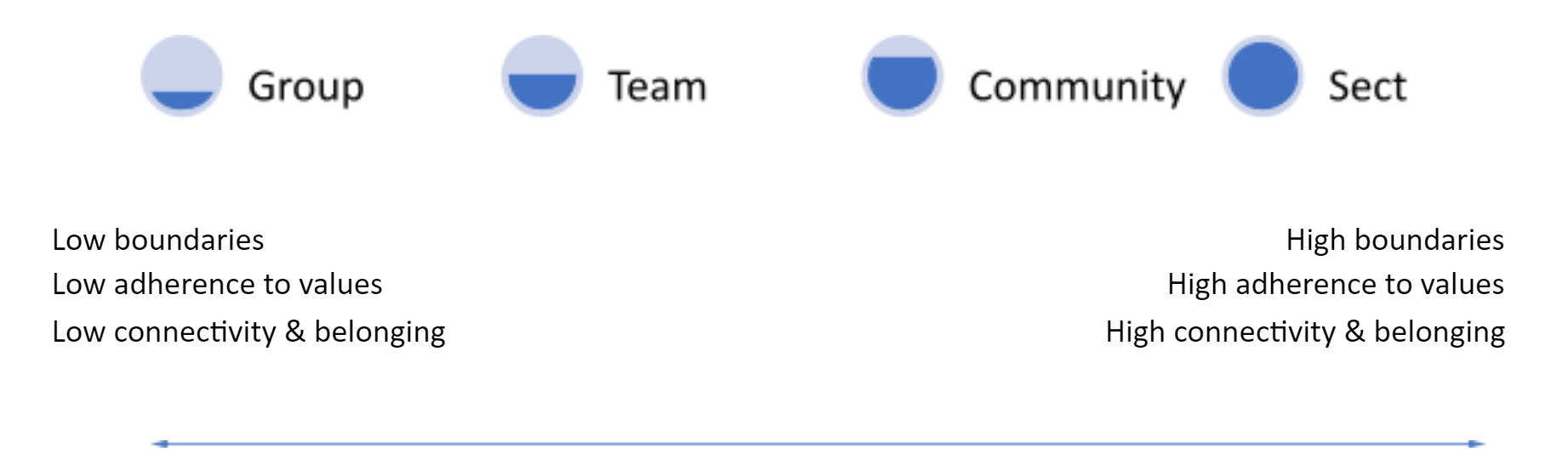

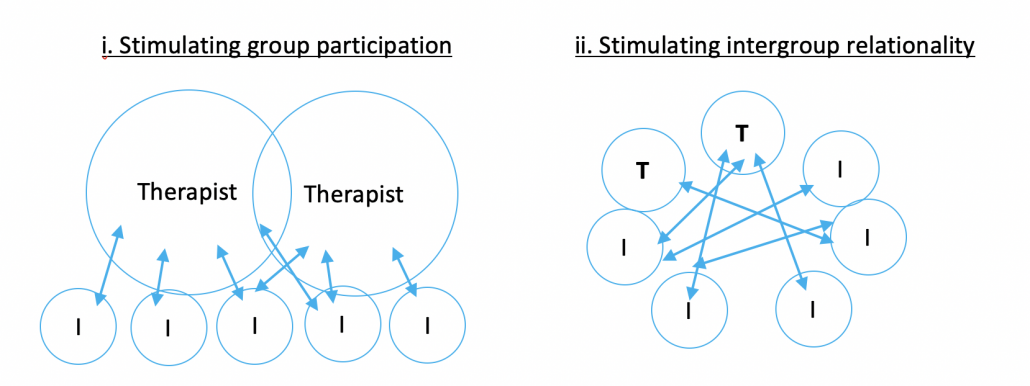

It has been empirically shown that our sense of self is not a fixed, reified and singular construct and experience. The Social Baseline Theory (SBT – Coan & Sbarra, 2011), for instance, shows that the way we conceive of our self is based on who we have around us. We are constantly evaluating the quality of our social environment and making judgments as to how much physiological resources (i.e. glucose) we need to use according to the task at hand. For example, if I have a few good friends around me, the bio-energetic cost of going up a hill will be less than if I am alone. In SBT they say our individual self then merges with others and forms a wider sense of a social sense, of which we become a part: “I am because we are” (Ubuntu saying). This shows that we evaluate threats and risks as being less dangerous with good friends (I know, it sounds so obvious now). However, most meditation circles in the West promote individual practice! In effect, they are encouraging us to go up that hill alone, which makes the difficulties we encounter in meditation be perceived as more difficult than if we were travelling with friends. Evolutionarily, we have become accustomed to be in the presence of others and therefore the baseline for feeling safe and well is to be a part of a larger pleasant social environment.

Figure 1. The individual and social environment overlap represent social baselines

(Gross, Medina-DeVilliers, 2020).

There is an overwhelming consensus in social and now clinical psychology showing that relationships are the most important factor, and by far, to build resilience and psychological health. Moreover, all of environmental safety and ease created by our peers frees us from having our hypervigilance neural networks online, and allows us to focus and ground ourselves deeper in our internal experience. This is why, at NeuroSystemics Dharma, we emphasize social meditation.

We make a lot of efforts to build a safe and compassionate community to support one another through the challenges of meditation. How difficult is it, for instance, to even take 15-20 minutes a day to sow down and practice? Very difficult for most of us. It’s challenging being with ourselves and develop these meditative skills of mindfulness, compassion, friendliness, joy and equanimity. Buddhist texts talk about “going against the stream” of our habitual patterns, and that takes effort. This effort is perceived as being less work if we do it together.

In our monthly 1.5h Dharma gatherings we teach meditation and practice in a community (like we used to before the modern industrial age). Our approach combines ancient Buddhist teachings with modern neuroscience and systemic analysis. To learn more and join us sign up here!

Many blessings and look forward to seeing you there.

Boaz

Somatic Dharma

“Feeling good is good!”

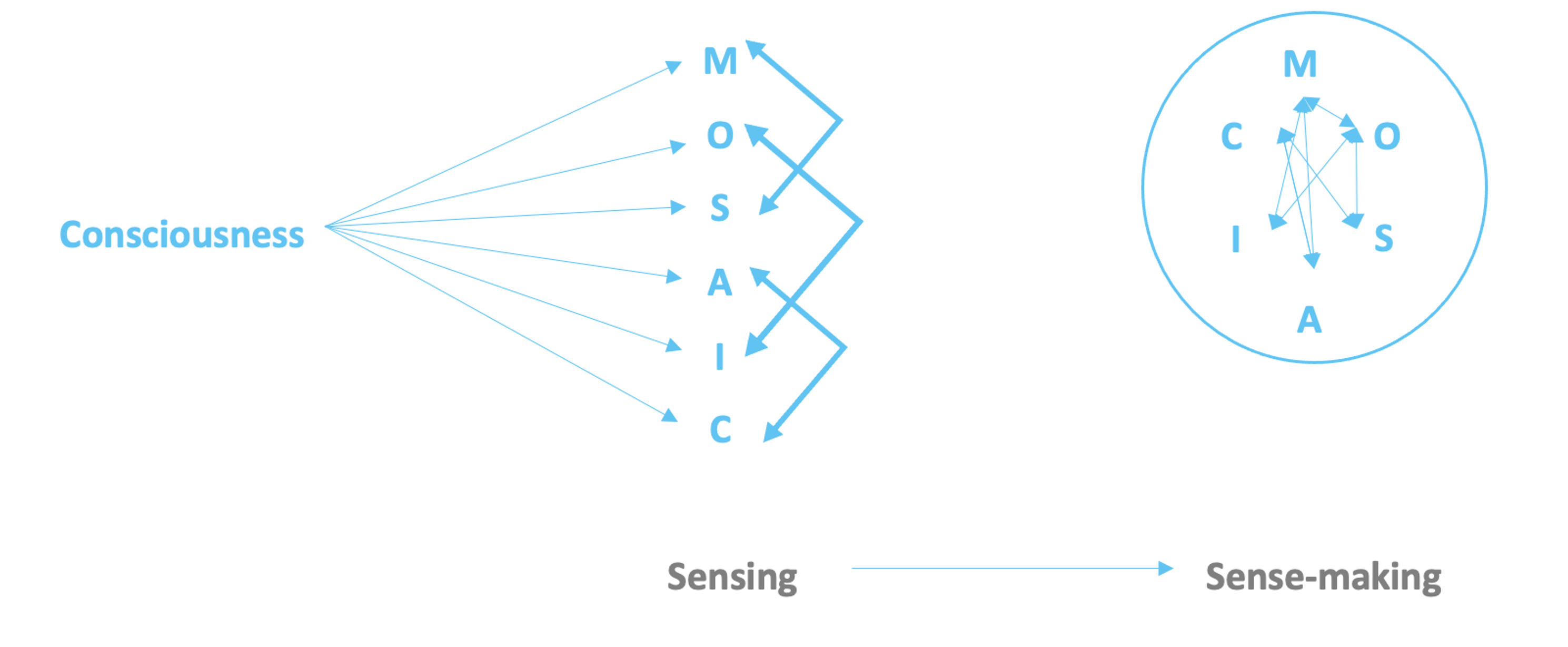

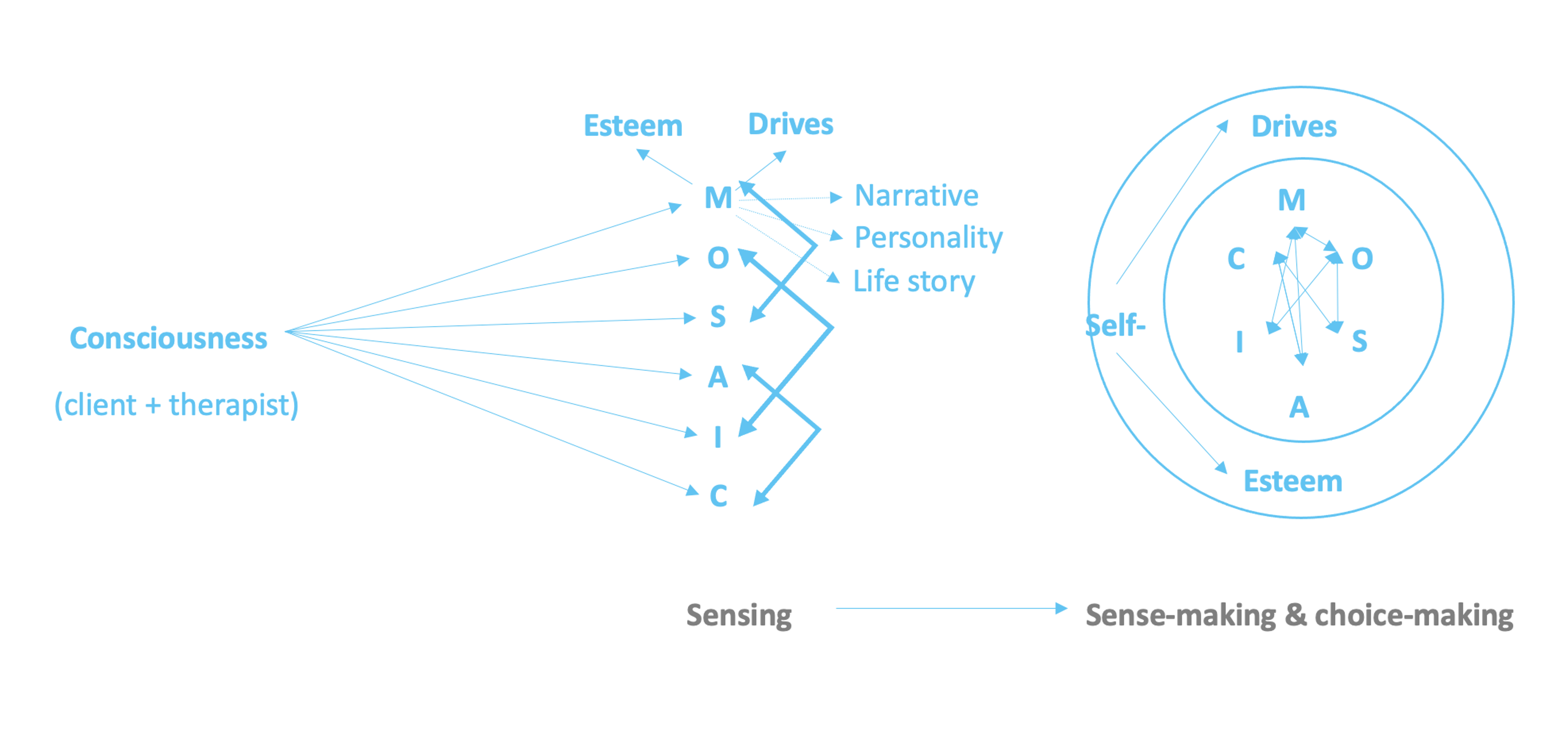

Over the course of 3.5 billion years of evolutionary history, life has become increasingly complex and organized. Simple life as bacteria is intelligent: they can distinguish materials in the environment which they like (i.e. sugar), from those which are dangerous. As humans, we have this same capacity for discernment for the environment of course, and we have it for our internal experience also. It’s called awareness, mindfulness or consciousness, and it’s a divine gift which can help us be happier and live a freer and more meaningful life.

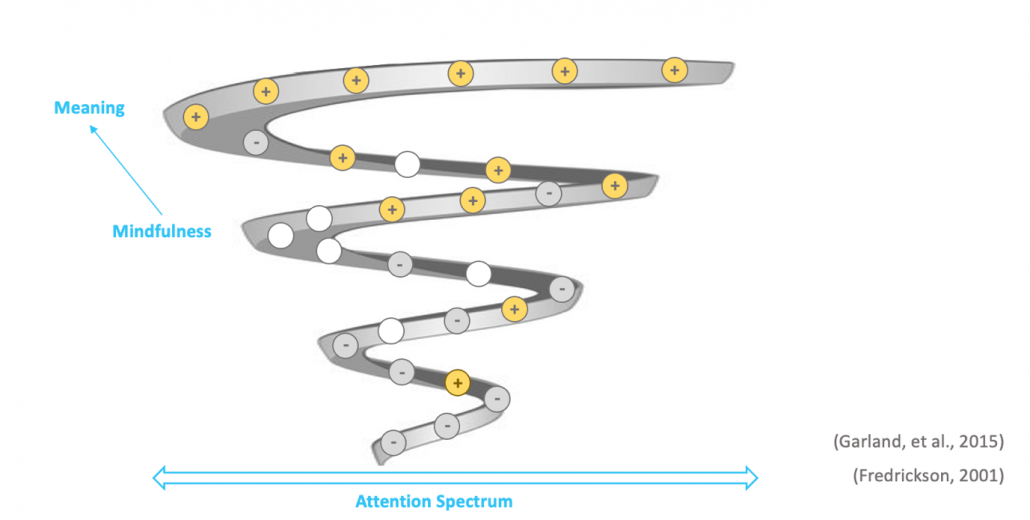

Mindfulness is a skill. It’s a complex quality of mind which life has developed in order to increase our chances of survival and enrich the texture of human experience. In Plato’s words, it contributes to making our lives better, more true and more beautiful. However, the quality of our mindfulness in each moment is interdependent with the state of our nervous system. Our state influences our capacity to be aware, and vice-versa. So as much as it is key to cultivate mindfulness skills in observing, discerning and clearly understanding our experience, it’s just as essential to support balanced and positive nervous system states. Fredrickson, a professor at the University of … and leading psychologist and neuroscientist, has shown that the happier we are, the broader our awareness and capacity to be with our experience (see figure 1). Therefore, feeling good is good!

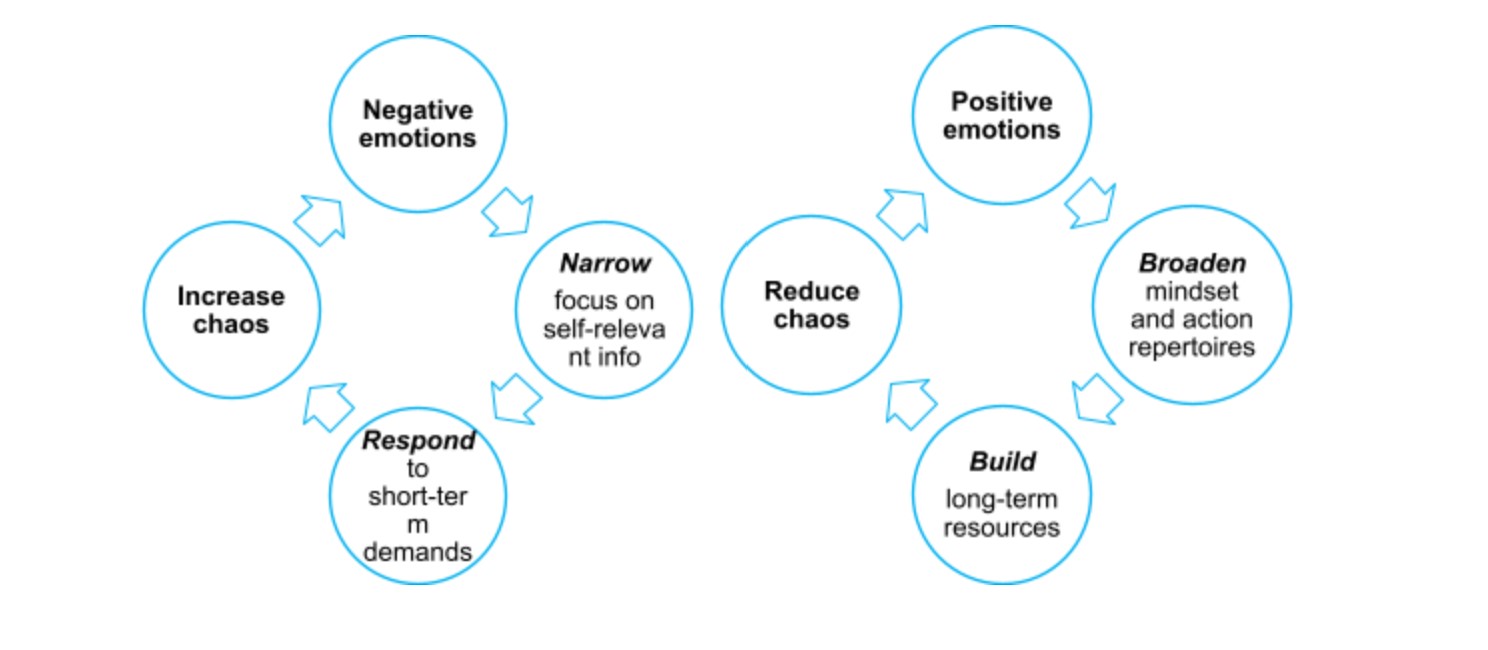

Figure 1. Broaden-and-build theory of positive psychology be Fredrickson, 2001: the worse we feel, the narrow our attention, and vice-versa, the better we feel, the more we can pay attention to. It is easier to derive meaning and richness in our experience when we feel good!

Easier said than done, of course. At NeuroSystemics Dharma, therefore, we equip ourselves we skills to navigate difficult nervous system states with somatic practices. We learn to find ways in which we can be here-and-now, relaxed and receptive, for example:

- Systematically emphasizing pleasure, enjoyment and ease

- Creating a welcoming environment and possibilities to orient in space to things which are pleasant

- Recognizing different nervous system states, fight-flight-freeze, to hold them with care and navigate through them skillfully

- Social meditation practices to ground one’s awareness in a field of kindness and collective engagement

- Providing an evolutionary context for meditation practice helping us understand the value of trusting connections and community

- Understanding basics of the nervous system to better regulate it

Delving deep inside ourselves to become our own best friends and widen our freedom is a long and often challenging journey. We need all the tools and support we can get! If you’d like to experience some of these, come and join us on our upcoming

Looking forward to see you there dear one.

Many blessings,

Boaz

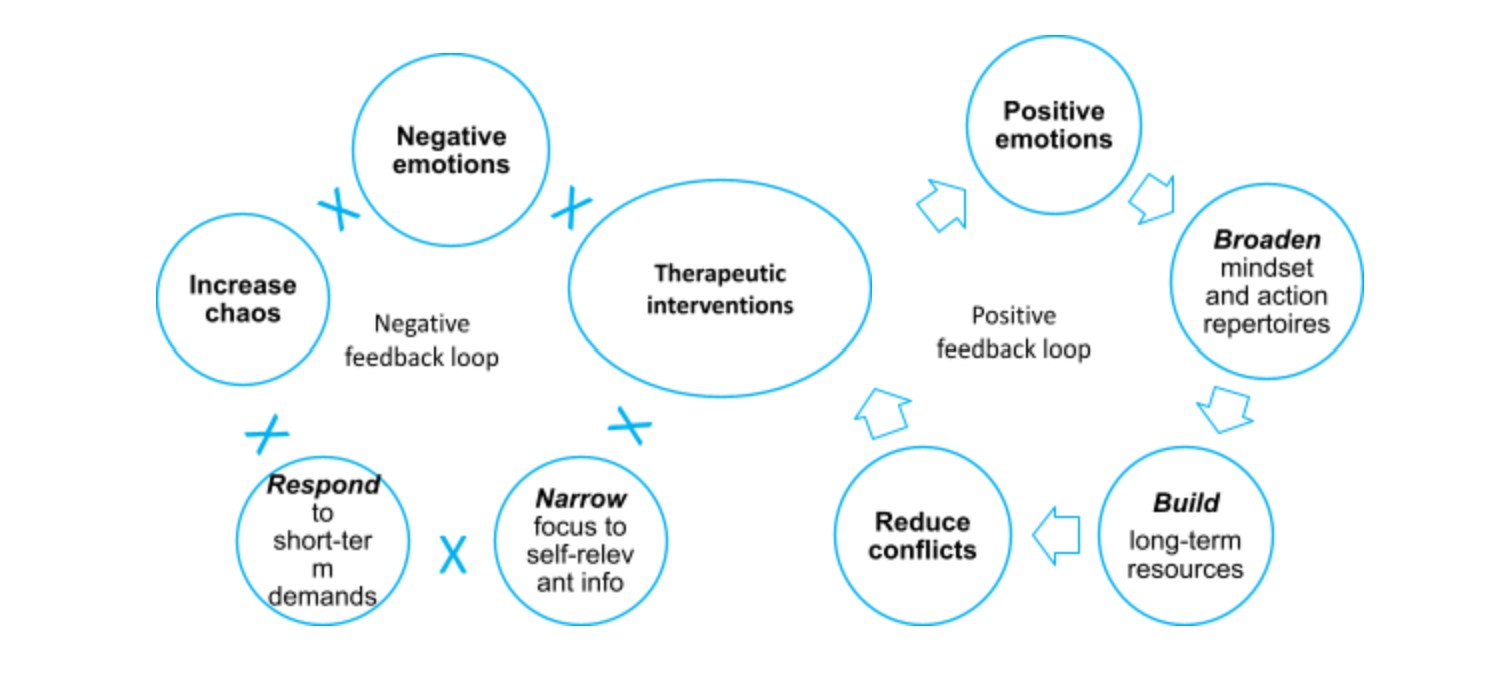

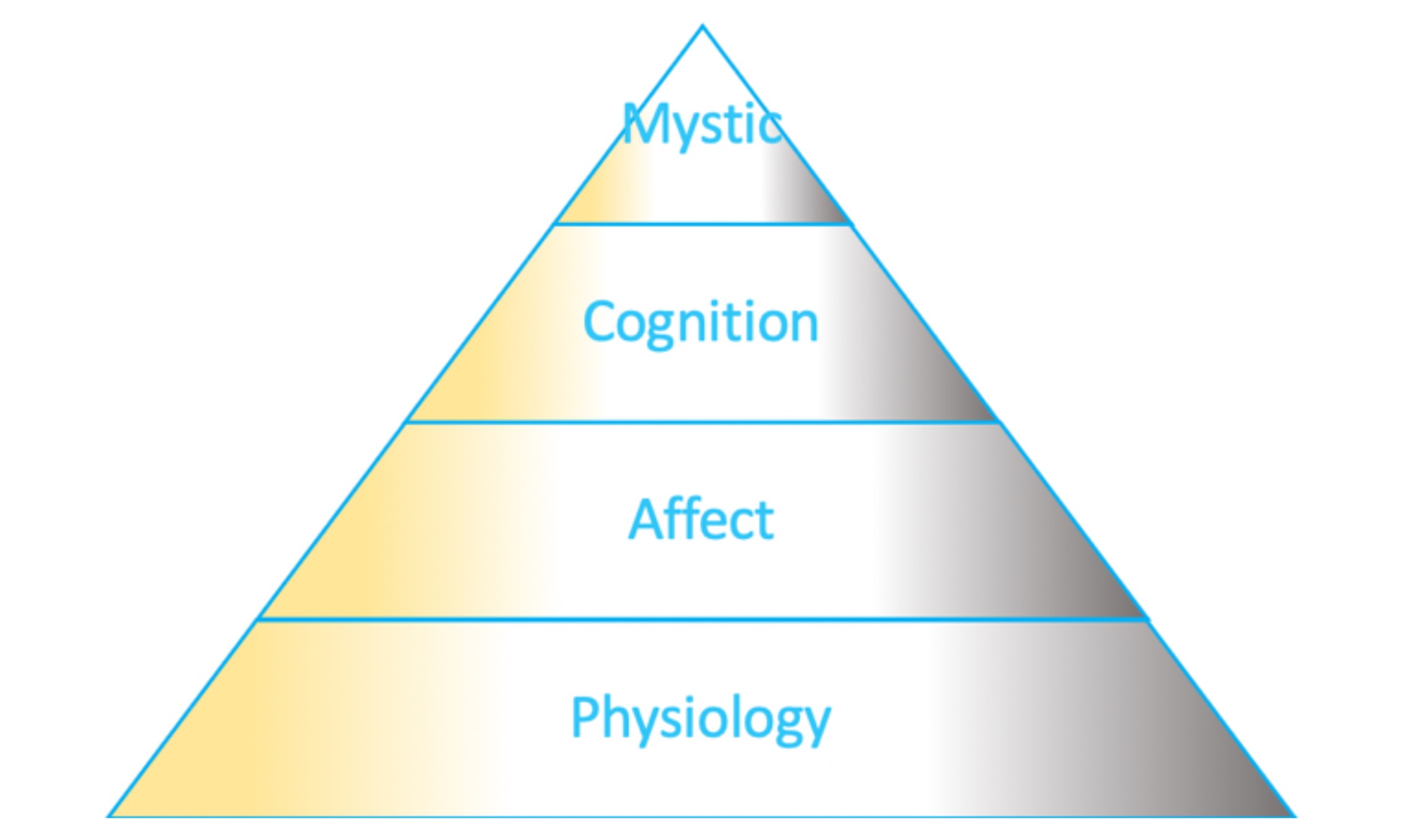

When clients come through the door, especially in the initial stages of therapy, their affect tends to be very dysregulated. High levels of negative emotional arousal will tend to colour their perception and experience very strongly. Therefore, a most urgent therapeutic task is to support clients regulate their bio-affective state. As clients become more settled and oriented to the present moment, it is possible to gently guide their physiology, affect and cognitive systems towards greater integration. The purpose of integration is to embody and strengthen skills of bio-affective deactivation, in order to build greater processing capacity in relation to challenging experiences.

This organismic learning gradually empowers a clients’ system to sense into the rich complexity of their experience, leaving no part out, and gradually inhabit more spaces of their psycho-somatic dynamics. Finally, this contained and embodied process of progressive complexification grows and builds until it reaches its next threshold of capacity, at a far-from-equilibrium state, leading to new emergent properties to arise: an insight, a new state, a previously unexplored perception. As an attempt to conceptualize this trajectory, NeuroSystemics proposes a 3-step therapeutic mapping: regulation, integration and liberation. This paper will provide some insights from the humanistic and contemplative sciences to explicate this journey.

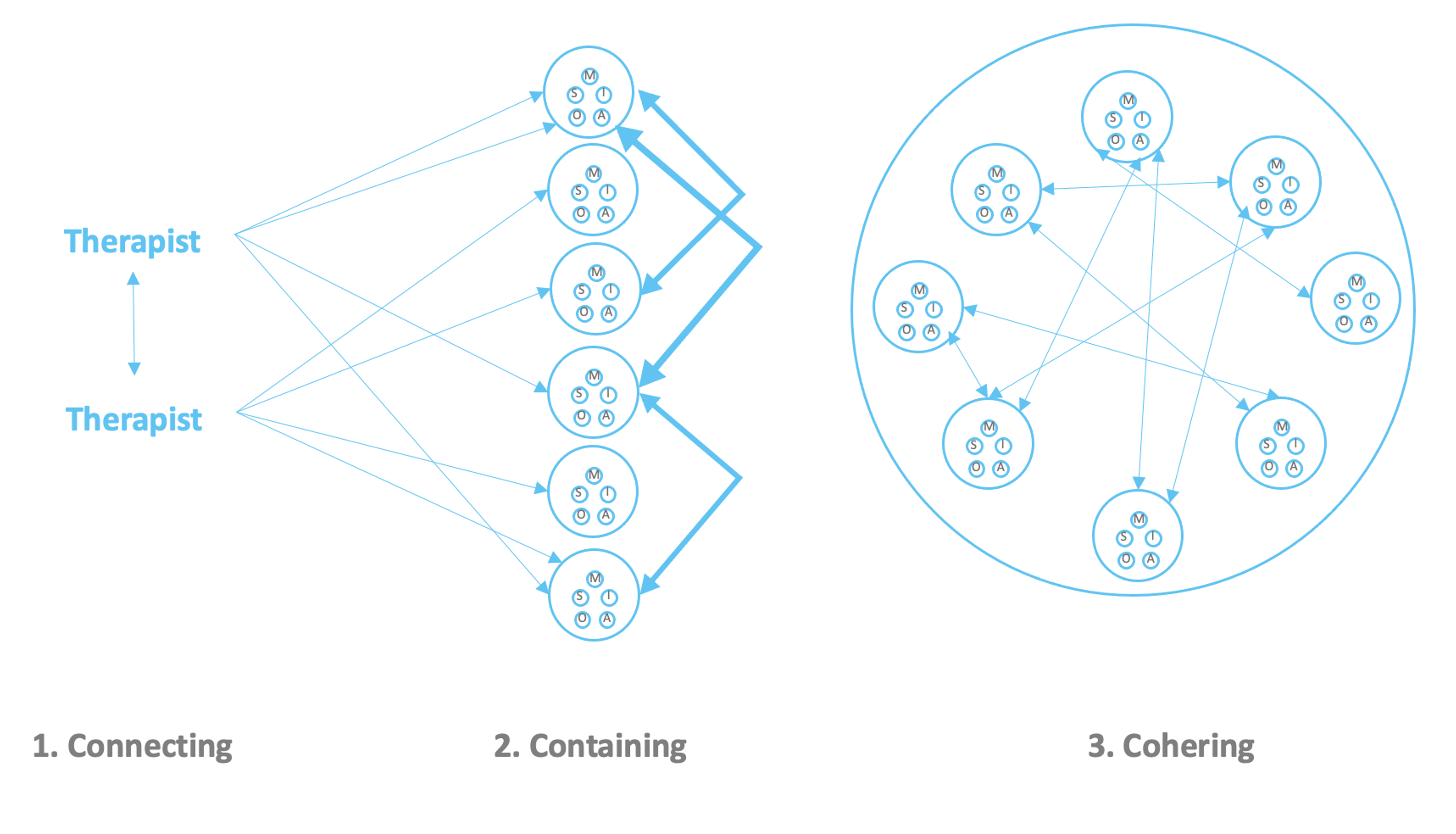

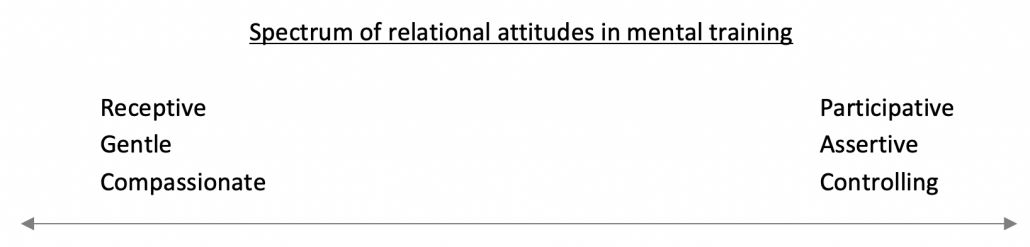

Therapist as model for regulation

One of the most powerful tools for therapeutic success is the therapist herself. The common factors research paradigm, analyzing over 70 years of clinical data, explains that the therapeutic alliance, comprised of (i) a trusting and compassionate therapist-client relationship, (ii) clear goals and (iii) tasks to achieve these goals, is more important that any specific technique. These relational factors, common to all successful therapeutic outcomes found in the literature, can be embodied through a series therapeutic attitudes: friendliness, compassion, joy and equanimity.

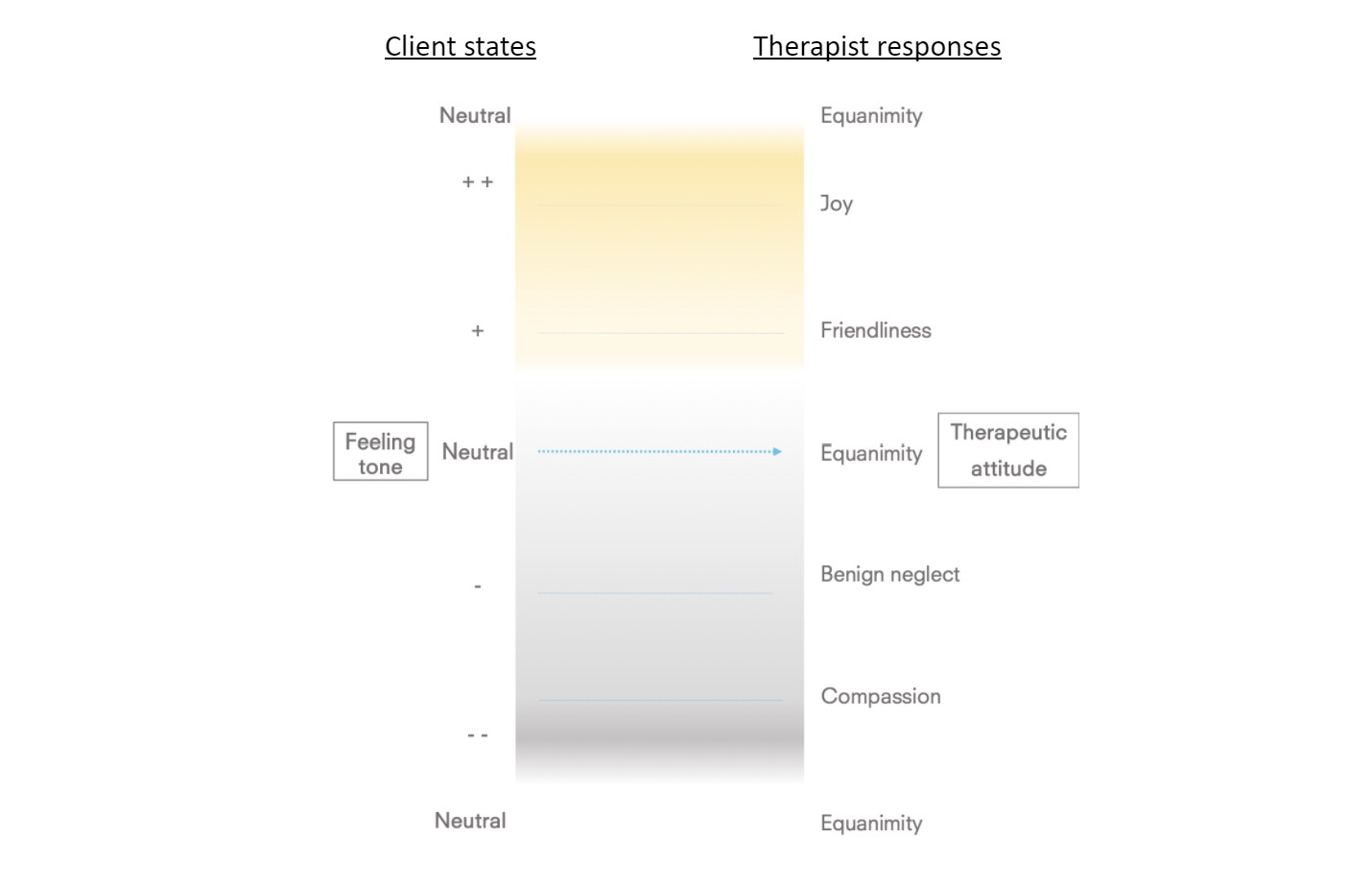

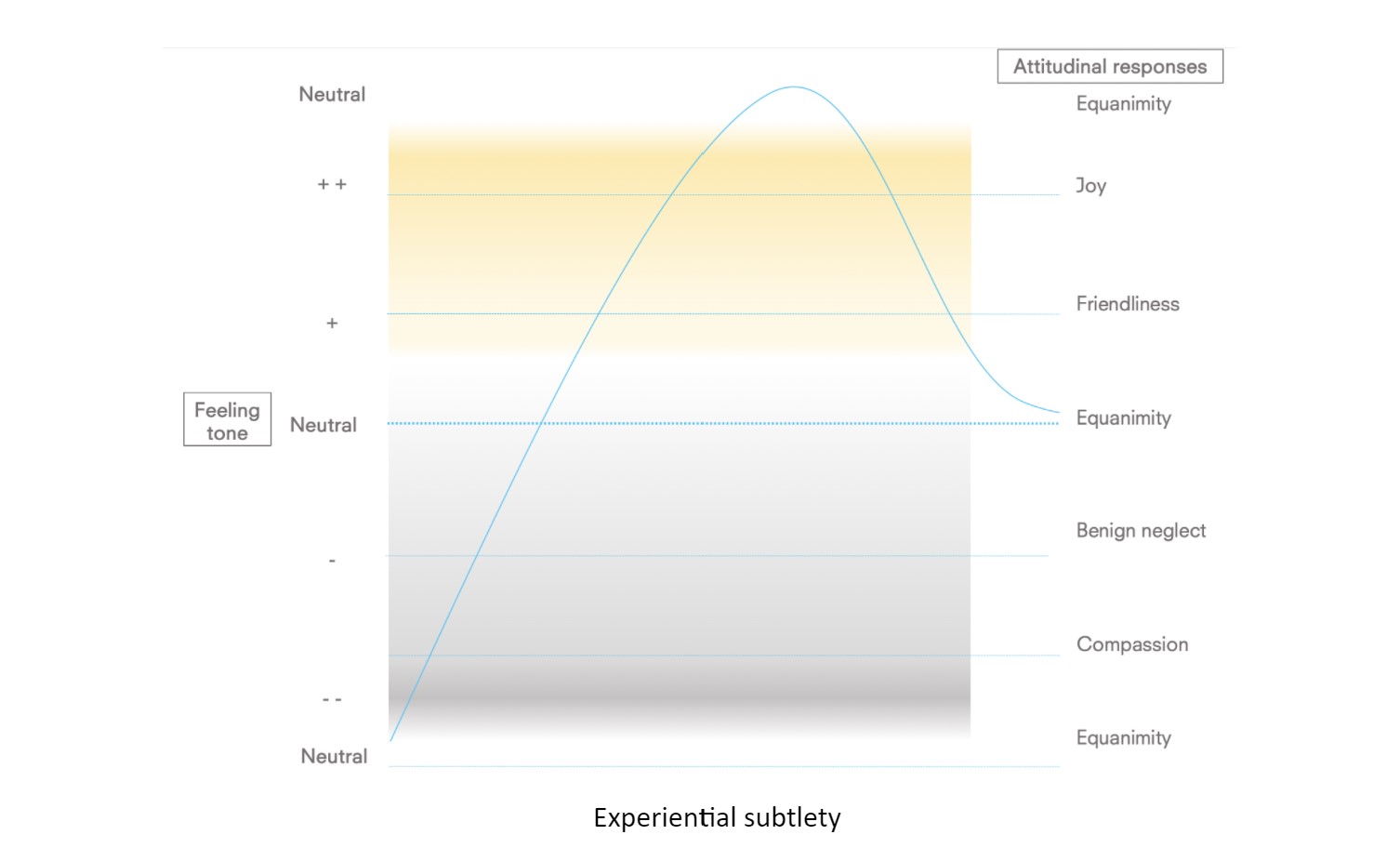

In Buddhist contemplative practice these correspond to “brahma-viharas” (Hinsdale, 2012), literally meaning divine abodes. These have many similarities to Carl Roger’s (Rogers, 1986) humanistic principles of congruence, empathy and unconditional positive regard, and offer a more differentiated map based on the client’s bio-affective shifts. Simply put, a therapist would attune and respond to their clients’ bio-affective state with a therapeutic attitude that would support greater ease, often corresponding to the following pairings:

Brahma-viharic qualities

In the face of negative affect, one of the most meaningful supports a client can receive is compassion (karuna). It is a positive state of mind where one feels joy at the possibility of lending a caring hand to one in need. In some cases, when the client is in the midst of distress, it may be possible to offer an attitude of benign neglect. The therapist’s attitude of genuine friendliness (metta) creates the most basic and fundamental affective space within which the client can feel safe and develop trust. Friendliness is mostly relevant for therapists to practice when clients experience somewhat pleasant feeling tones. As a principle, as the therapeutic process evolves, therapists’ higher-level feeling tones (joy as the highest) will become attuned responses to clients’ lower-level affective tones (very negative as the lowest). Therefore, over time, it will progressively be possible to expand the quality of friendliness to neutral and negative feeling tones.

The therapeutic encounter offers many moments of joy (mudita), which is a skill where the therapist attunes to the client’s joys, even momentary upsurges of joy – feeling joy in regard to the joy of the client. As with so many causal processes in complex systems, they are bi-directional or even multi-directional. At times, therefore, it can work in the other direction: the therapist’s joy can be contagious enough to help the client rise up to that level of affective intensity. Equanimity (upekkha), synonymous with equipoise, is a balancing quality helping to bring an evenness of mind, an investigative quality to all negative and positive experiences.

Positive emotions have shown beneficial effects in terms of their “undoing” of negativity. Fredrickson’s “undoing hypothesis” is based her empirically tested Broaden-and-Build theory (2001). The key element here is to understand the positive and negative feedback loop processes at play.

Figure 2. Positive feedback loop processes for positive & negative emotions

Experiencing positive emotions internally first help to broaden one’s cognitive and behavioural repertoires. Brain imaging studies have shown that positive emotions broaden the scope of physiological visual attention and expand people’s repertoires of openness to new experiences. At the interpersonal level, induced positive emotions increase people’s sense of “oneness” with close others and their trust in acquaintances

Benign neglect, compassion and equanimity, respectively, can be reflected as a progressive gradation of support when a client experiences difficult emotions. Friendliness, joy and equanimity, respectively, are positively reinforcing attitudes towards the clients’ progressively pleasant affective tonalities. It is initially through the therapist’s support and explicit attitudinal intervention that a client can learn to reduce their challenging states, down-regulating affective processes. By modelling an attunement and responsiveness to clients’ nervous system states, affect and socio-cognitive processes through the embodiment of brahma-viharic attitudes, clients will eventually learn to regulate their own waves, changes and movements in their bio-affective rhythms. As the client understands the importance of this attitudinal practice (clarifying this as a goal of therapy), their task is to learn to support and regulate themselves in the therapeutic setting and in their daily life.

Figure 3. Therapy-generated affective positive & negative feedback loops

In effect, positive emotions will develop a momentum via positive feedback loops of broadening and building (escalatory process), and negative emotions will be reduced both in their intensity and frequency via negative feedback loops of narrowing and responding (de-escalatory process).

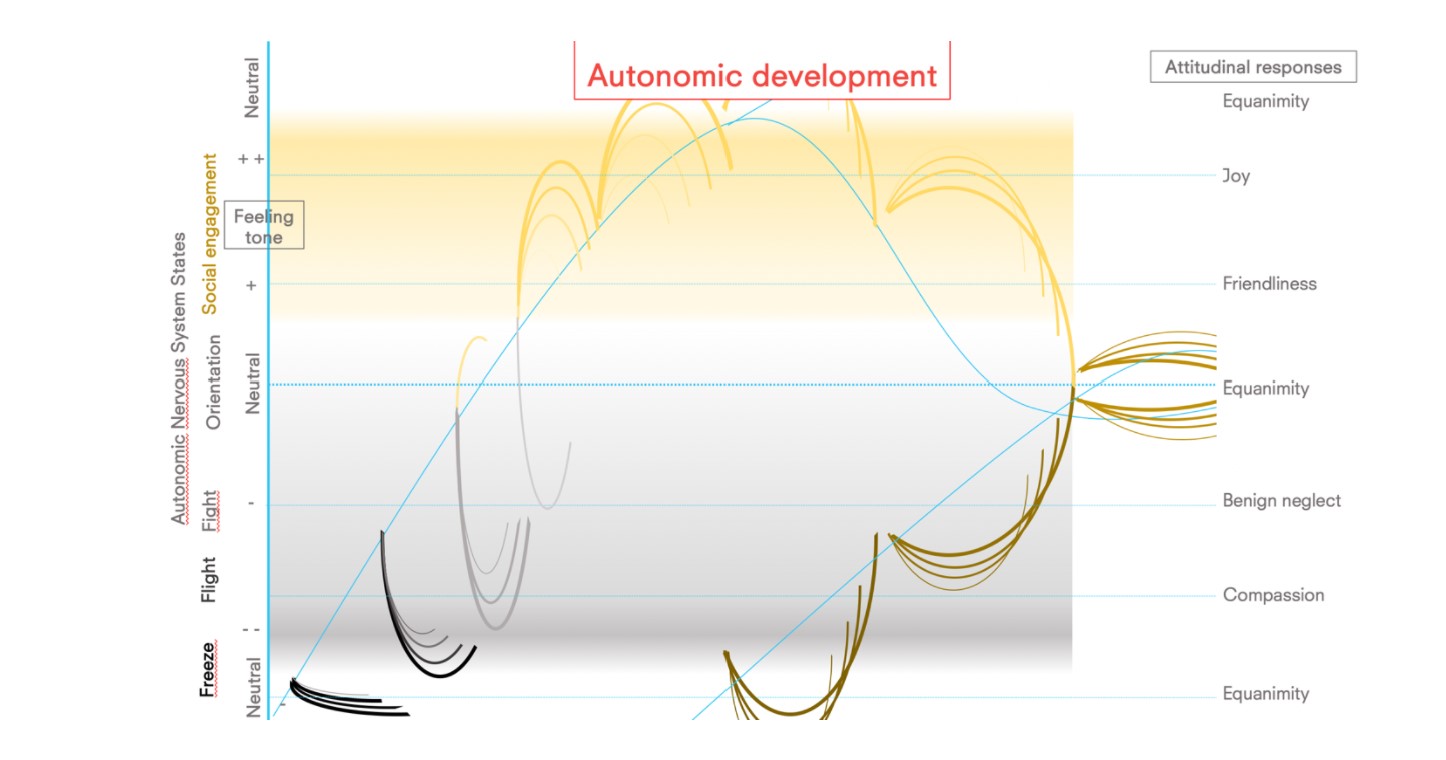

A transcendent trajectory

As clients begin their therapeutic journey, regulation entails a down-regulation of negative states. As the therapist, through their quality of presence, embodiment and modelling of brahma-viharic attitudes, clients are able to skillfully negotiate challenging bio-affective states, and upregulate positive states. The below diagram describes this journey as a rising curve to the highest affective tonalities, followed by a reduction in the intensity. The declining curve, indicating a reduced intensity in positive affect, is informed by Buddhist meditative maps of jhanas. These are states of increasing happiness, absorption and refined perception.

The Buddhist path to de-pathologize the psyche implies a gradual clarification, a ridding of confusion, a refinement of perception of one’s direct experience. The affective trajectory in the diagram, from left to right, describes a progressively less constructed, more subtle nature of phenomena. This means that very negative experiences are more constructed, more entangled, more fabricated than positive experiences, which are further along the process (more to the right). As affect matures and deepens, it reaches even more subtlety and stillness, taking form in equanimity, and progressively deeper states of equanimous experiences. These are experienced as higher forms of happiness the positively-valenced states preceding them, involving non-dual perception and further sensitivity to the emptiness of inherent existence of experience and phenomena.

Figure 3. Experiential subtlety

Trauma & jhana

There are important implications and correlations with this conceptual framework and that of trauma healing. Trauma occurs as a result of a nervous system overwhelm of sympathetic arousal in the autonomic nervous system (Porges & Buczynski, 2011). This leads to the nervous system to transition from sympathetic (fight and flight) to dorsal vagus (freeze) activations. A client in freeze will experience a much-reduced access to sensation, affect and orientation, and reduced sensitivity to mental images and cognitive content.

Interestingly, scientific evidence is emerging showing similarities in neurobiological substrates of jhanas and freeze states, except that these states are profoundly resourceful and transformative. They differ in three respects: (i) the preexisting conditions leading to its emergence (enjoyment training vs shock), (ii) the conceptual framework attempting to understand them (refinement of understanding the phenomenal nature of experience vs pathology) and (iii) the contiguous neurobiological networks (isolated vs interconnected) and physiological rhythms of state transition (rapid and erratic vs smooth and systematic). Freeze, a system evolutionarily designed to process backlog of sympathetic overstimulation, then, may also be a profound opportunity for cosmic connectivity and transformative meaningfulness.

The threads on the diagram, starting black and only rising, shifting through shades of grey, yellow and culminating in gold, describe the client’s progressive movement of integrated bio-affective regulation. Freeze states appear at the bottom of the graph, and clients often begin their therapeutic engagement with strong patterns of freeze, as described by the thick black threads.

Conclusion

Therapeutic presence with brahma-viharic attitudes, followed by the client’s self-organizing attunement to bio-affective states, and regulatory capacity of them, enables the process to evolve towards greater positivity (in thickening yellow threads). After reaching the peak of positivity, the system is able to experience the pendulation between approach (social engagement) and avoidance (fight-flight-freeze) states, with increasing rhythmicity and synchronicity. These wavic patterns help the process of somatic integration, leading to new levels of bio-affective agency emerging when the threshold for holding capacity of the complex interactions has been reached.

May this article be of benefit for all beings!

You can learn more about the application of these evolutionary and systemic models, their associated neuroscientific empirical research, practice and clinical interventions along with time for practice in our workshops, courses and trainings at www.neurosystemics.org.

Together we go further.

References

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American psychologist, 56(3), 218.

Hinsdale, M. J. (2012). Choosing to love. Paideusis, 20(2), 36-45.

Porges, S. W., & Buczynski, R. (2011). The polyvagal theory for treating trauma. Webinar, June, 15, 2012.

Rogers, C. R. (1986). Carl Rogers on the development of the person-centered approach. Person-Centered Review.

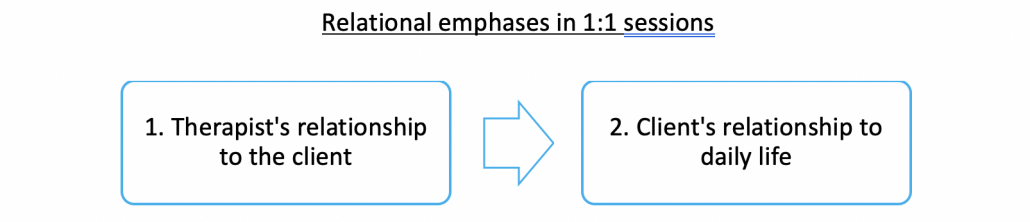

The purpose of therapy and coaching is to end the need for therapy or coaching. Our clients will come to see us because they need our help. In the initial stages, most of them will be dependent on us to some extent – they will re-enact their insecure/avoidant/ambivalent attachment patterns (see upcoming post for a description of attachment patterns), require some structure outside of their psychic capacity (clinical context), need to orient to a more organized bio-psychosocial system (the therapist) – and it is our duty to support them in these critical initial stages.

Our modeling of attuned humanistic attitudes and therapeutic postures of compassion, equanimity, friendliness and joy will help to reprogram the developmental mis-attunement they will have suffered throughout their life (through complex trauma, low socio-economic conditions, authoritative education, etc). Our clients’ trust in the therapeutic alliance will give us leeway to help shape:

- their internal responses to nervous system sympathetic and parasympathetic arousal and thresholds (somatics);

- their navigation of dark (negative) and lighter (positive) affective experiences (affective development);

- a higher self-esteem through self-acceptance, encouraging creative outlets, orienting them towards life-fulfilling goals and a (self-determined) ethical livelihood (cognition and self-representation), as well as;

- more securely attached relational patterns and deeper belonging in interpersonal bonds (relationships).

An empowering trajectory

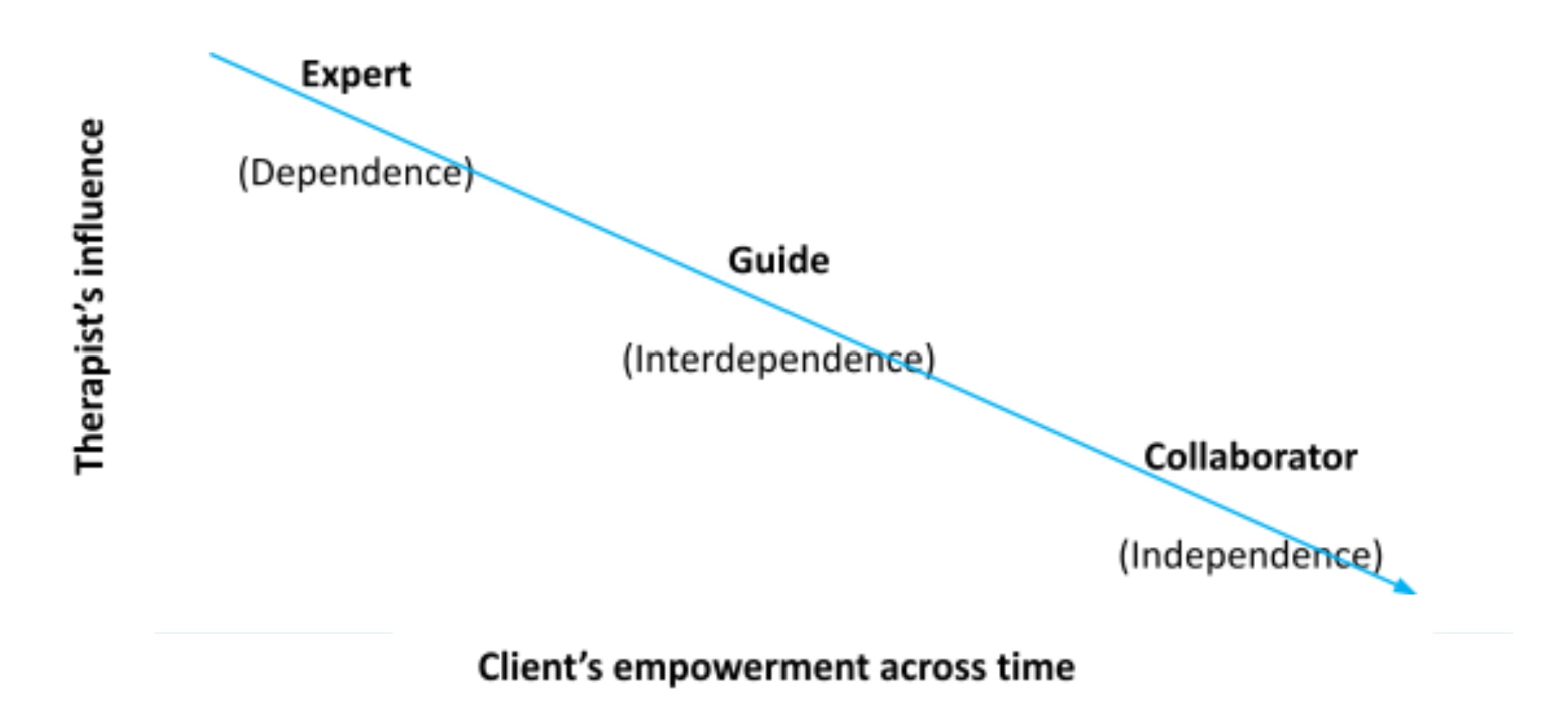

In order to be free from therapy or coaching, our clients will need to build increasingly self-organizing capacities on all the levels described above (somatics, affect, cognition and relationships). As this empowerment process occurs, they graduate through different stages of dependency: dependence, interdependence and independence (see diagram 1).

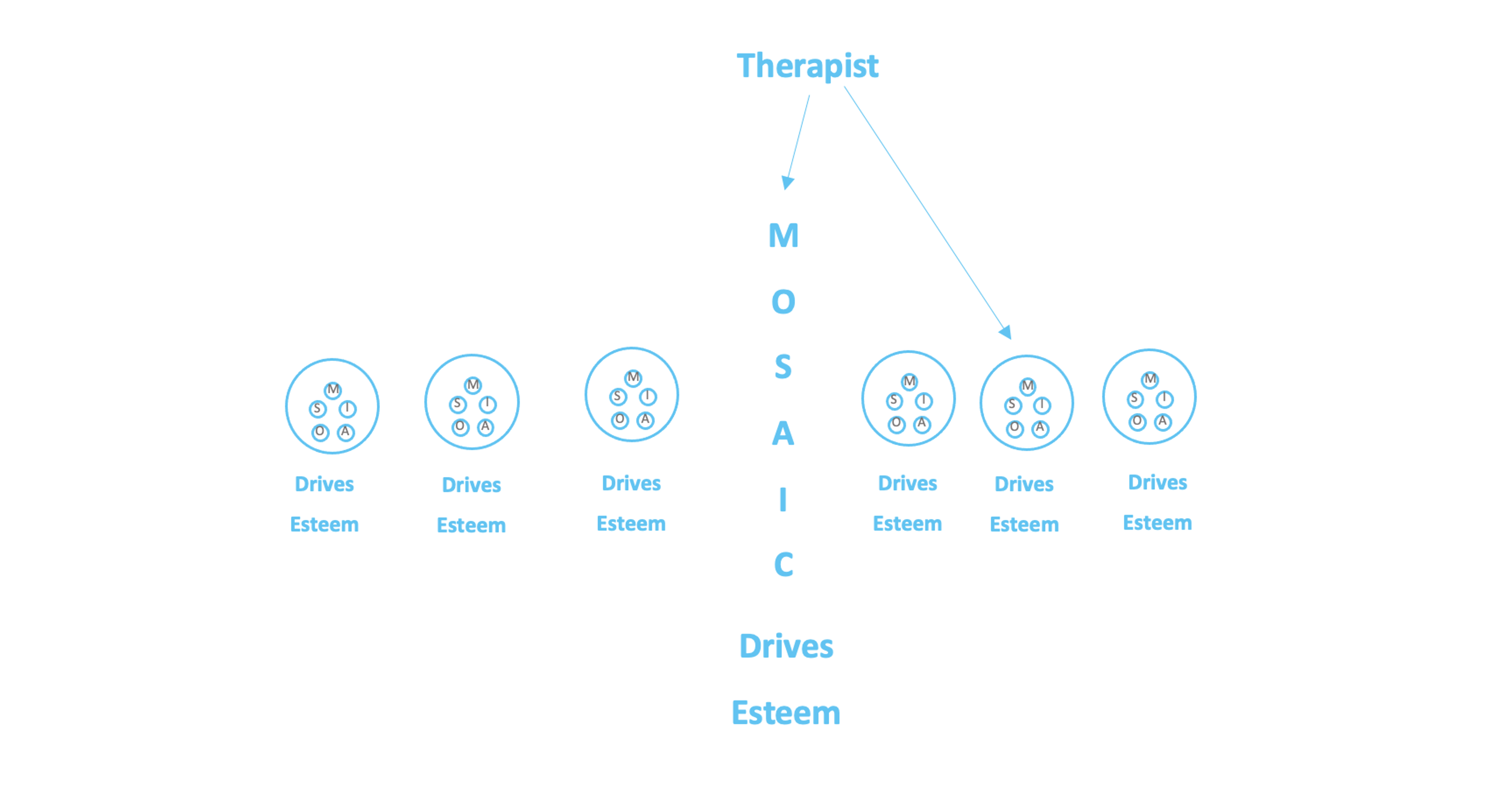

Diagram 1. The therapists’ postures as clients integrate the empowering therapeutic experiences

Diagram 1. The therapists’ postures as clients integrate the empowering therapeutic experiences

This linear therapeutic progression initially follows a top-down structure (client dependence) to a balanced power position (therapist nourishing clients’ existing resources), to a collaborative structure (therapist bringing useful, but replaceable, spaces and inputs) in its final stage of development. As a cyclical process, the therapeutic relationship will have many implicit and explicit collaborative moments in the early dependent stages, and still some areas where the therapist will remain an expert at the ‘independence’ stage. This linear progression is only a rough schema of a complex, multifaceted and omni-relational process of development.

As the therapeutic process begins, a therapist will use their influence in various ways (i.e. attending, tuning, somatic mirroring, positive reinforcement, vulnerable self-disclosures) to feedback to the client all the external projections towards a multi-faceted empowerment (somatically, affectively, cognitively and relationally – more on this in a future blog). As the therapy unfolds, and clients integrate these empowering clinical interventions, the balance of power shifts (interdependence stage), and therapists can point more explicitly to the clients’ resources and skills, and further their organismic confidence.

At the neurobiological level, the skillful furthering and development of the client’s intrinsic organismic movements in bio-psycho-affective states gives their organism the signal “I can rely upon myself, I can count and depend on myself,” independent of the therapist’s presence or interventions. The building of self-organising capacity is one of the key factors for clients to integrate their experiences in therapy into daily life and sustain deep and meaningful transformations. As Otto Rank said, “the purpose of the therapist is to help the person to develop into that which they are” (Rank, 1936). Achieving this enables independence, ending the need for therapy. HURRAY!

May this article be for the benefit of all being.

You can learn more about the application of these evolutionary and systemic models, their associated neuroscientific empirical research, practice and interventions along with time for practice in our workshops, courses and trainings at www.neurosystemics.org.

Together we go further.

References

Rank, O. (1936). Will therapy. An analysis of the therapeutic process in terms of relationship.

A wide-ranging review of the past 60 years of clinical practice (i.e. Baldwin, Wampold & Imel, 2007) shows that the number one factor for therapeutic success is a high-quality alliance between therapist and client, and a clarity around the goals and tasks of therapy. In this article we will provide:

- a meta-conceptual framework explaining the spectrum of therapists’ influence over the course of therapy

- specific questions, stemming from humanistic sciences (Maslow & Rogers, 1979), which help clients be more empowered, build more autonomy and trust of their own capacity

Meta-conceptual framework of clinical interventions

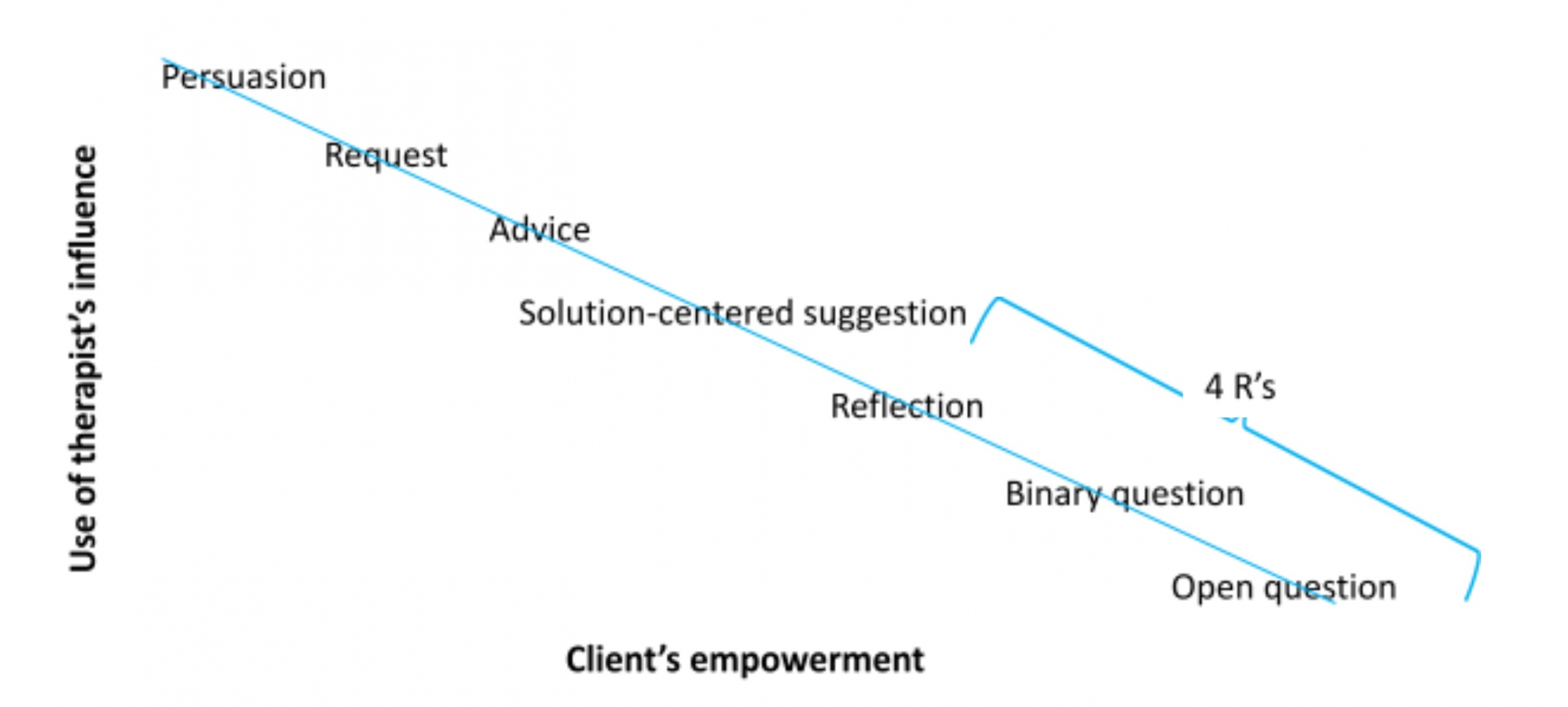

The initial goal of therapy is to help the therapist gain the client’s trust to build a strong alliance and raise epistemic confidence (the clients’ confidence in themselves to find their own solutions). This involves a progressive development of intimacy and trust between the therapist and client, which can be realized with the following options of therapeutic possibilities (see Diagram 1).

Diagram 1. Spectrum of therapeutic interventions as a client becomes more empowered.

Diagram 1 represents the spectrum of therapeutic interventions from more power-rich (though not power-over) to more empowering forms. This map is linear, and helpful to understand the overall journey of a client, with specific clinical interventions. However, it is important to note that as organisms, with our complex structure and non-linear cycles, we will need far more attunement and sensitivity than a simplistic formula such as this one to succeed in empowering our clients. Nevertheless, this may initially provide a helpful structure.

When a client is severely unwell, it will be helpful to provide a strong frame and use our suggestive authority to help strengthen their socio-emotional container. The interventions of persuasion (i.e. “you will need to take medication”), requests ( i.e. “please make sure you go for a walk in nature everyday”)and advice-giving (i.e. “I would recommend that you have some rest after our session”) will tend to fall in this category.

Solution oriented proposals will orient our clients strongly towards the positive, the constructive, the skilfull (i.e. “imagine you were able to achieve your goal, how would that be for you?”). It helps support a deeper sense of embodiment, confidence and belief in their agency and ability.

The 4 R’s follow: reformulate, recontextualize, review, and reinforce:

- Reformulate: using an impressionist form and tone, reflecting/mirroring back to the client what has been heard to show the therapist understands what they have shared and helps build/restore the therapist-client collaboration and dance. Reformulations also help structure the narrative and/or present emotion, key points can be amplified, emphasize the posture of curiosity and not-knowing, the therapist can also make helping additions and use different wordings to broaden the discourse, while checking the client shares these developments. In most reformulations, there is the formulation of a relatively complex hypothesis relevant to the client. These are sub-categories of reformulation:

- Simple repetition (parrot): reflect back word-for-word what the client shared, as precisely as possible (usually for high arousal disclosures).

- Verification: verifying the meaning of certain sentences, feelings, descriptions

- Simple reflections: neutral reformulation

- Double reflections: repeating two often contradictory points of view or experiences to underline ambivalence (refrain from using “but”)

- Recontextualise: help bring greater precision and specificity to the client’s situation (difficulty or ease). Asking for examples or situations that are space and time bound enables a crossover from a more conceptual, verbalized cognitive generality to an embedded and embodied experience. This promotes a re-centering of attention on the experiential qualities of the discourse/narrative and allows give opportunities for the client to feel recognized and understood by the therapist. Here are some examples:

- “Could you give me a recent example of what you are describing?”

- “When was the last time this occurred?”

- “How does this manifest in your daily life?”

- Review/Recap: summarise the client’s sharings to make sure they have been understood. They can occur at any time and may be very brief (2-3 sentences) or quite in-depth (a few minutes). Recapping helps the client feel understood and build a common vision and therapeutic alliance. They can be particularly useful at the end of a session to start slowing down and reducing new input into the session, as well as revisiting some of the key themes and moments of the session. The client participation can also be encouraged by asking them to review the session(s) themselves, saying for example:

- “What have been the key learnings/takeaways/experiences from this session?”

- “What do you make of all of this?”

- “In one word, how would you sum today’s exchange together?”

- Reinforce: positive reinforcement is part of a shaping and conditioning paradigm which aims at increasing the level of confidence in certain pattern, thereby raising the probability of that skillful behaviour to arise again. It is a powerful tool initially to strengthen the therapeutic alliance, and then supports the client’s feeling of self-efficacy. They offer important spaces for satisfaction, appreciation and celebration in the midst of the client recounting challenging situations. One can reinforce:

- Facts: underline a client’s action or behaviour in the past or in the present, which they have done or refrained from doing.

- People: emphasize the helpful qualities present as the client is sharing.

- Affect: recognizing suffering, normalizing it and offering encouragement and compassion (i.e. “in this situation, it is normal to feel…”)

May this article be for the benefit of all beings.