When clients come through the door, especially in the initial stages of therapy, their affect tends to be very dysregulated. High levels of negative emotional arousal will tend to colour their perception and experience very strongly. Therefore, a most urgent therapeutic task is to support clients regulate their bio-affective state. As clients become more settled and oriented to the present moment, it is possible to gently guide their physiology, affect and cognitive systems towards greater integration. The purpose of integration is to embody and strengthen skills of bio-affective deactivation, in order to build greater processing capacity in relation to challenging experiences.

This organismic learning gradually empowers a clients’ system to sense into the rich complexity of their experience, leaving no part out, and gradually inhabit more spaces of their psycho-somatic dynamics. Finally, this contained and embodied process of progressive complexification grows and builds until it reaches its next threshold of capacity, at a far-from-equilibrium state, leading to new emergent properties to arise: an insight, a new state, a previously unexplored perception. As an attempt to conceptualize this trajectory, NeuroSystemics proposes a 3-step therapeutic mapping: regulation, integration and liberation. This paper will provide some insights from the humanistic and contemplative sciences to explicate this journey.

Therapist as model for regulation

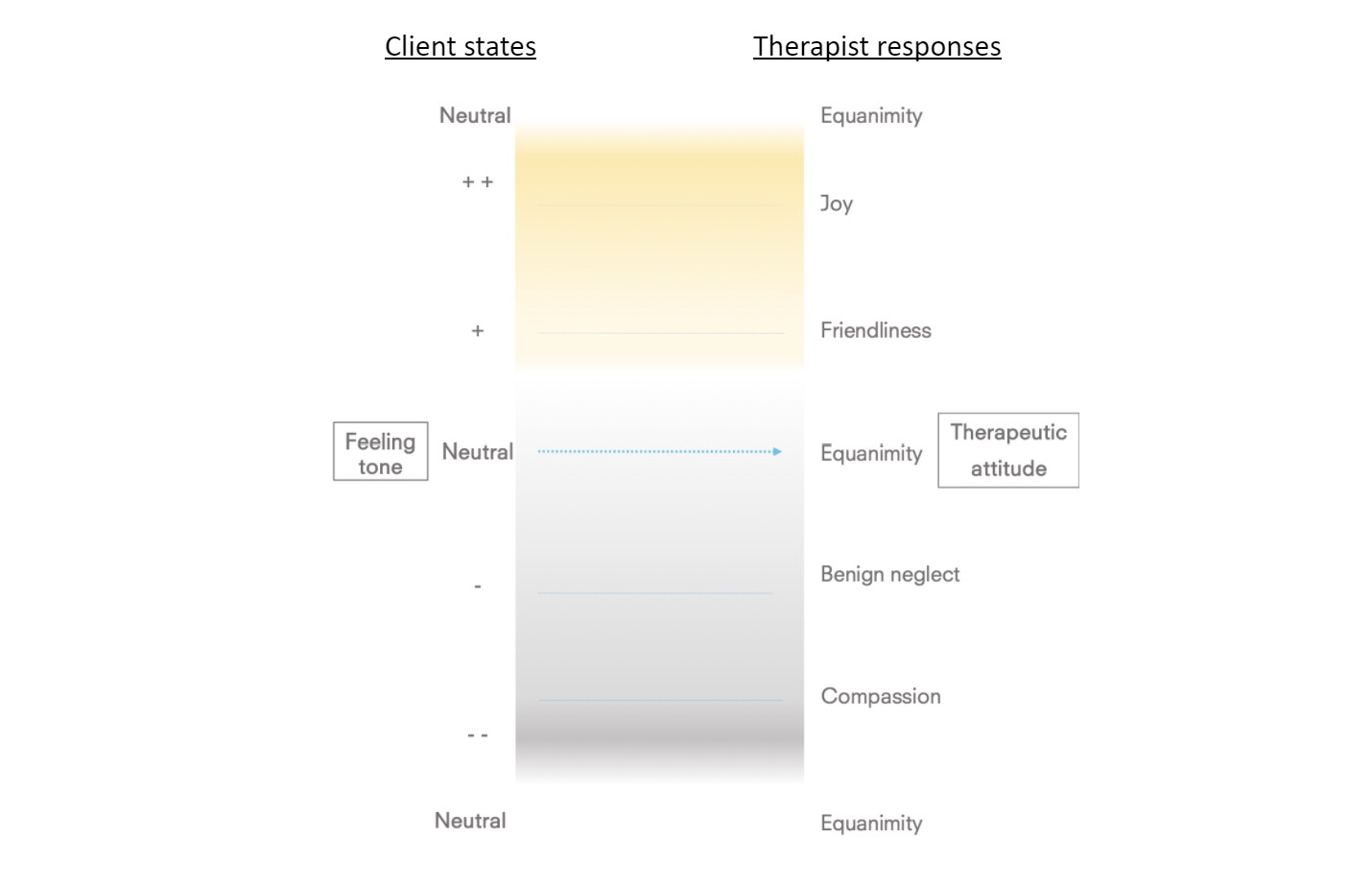

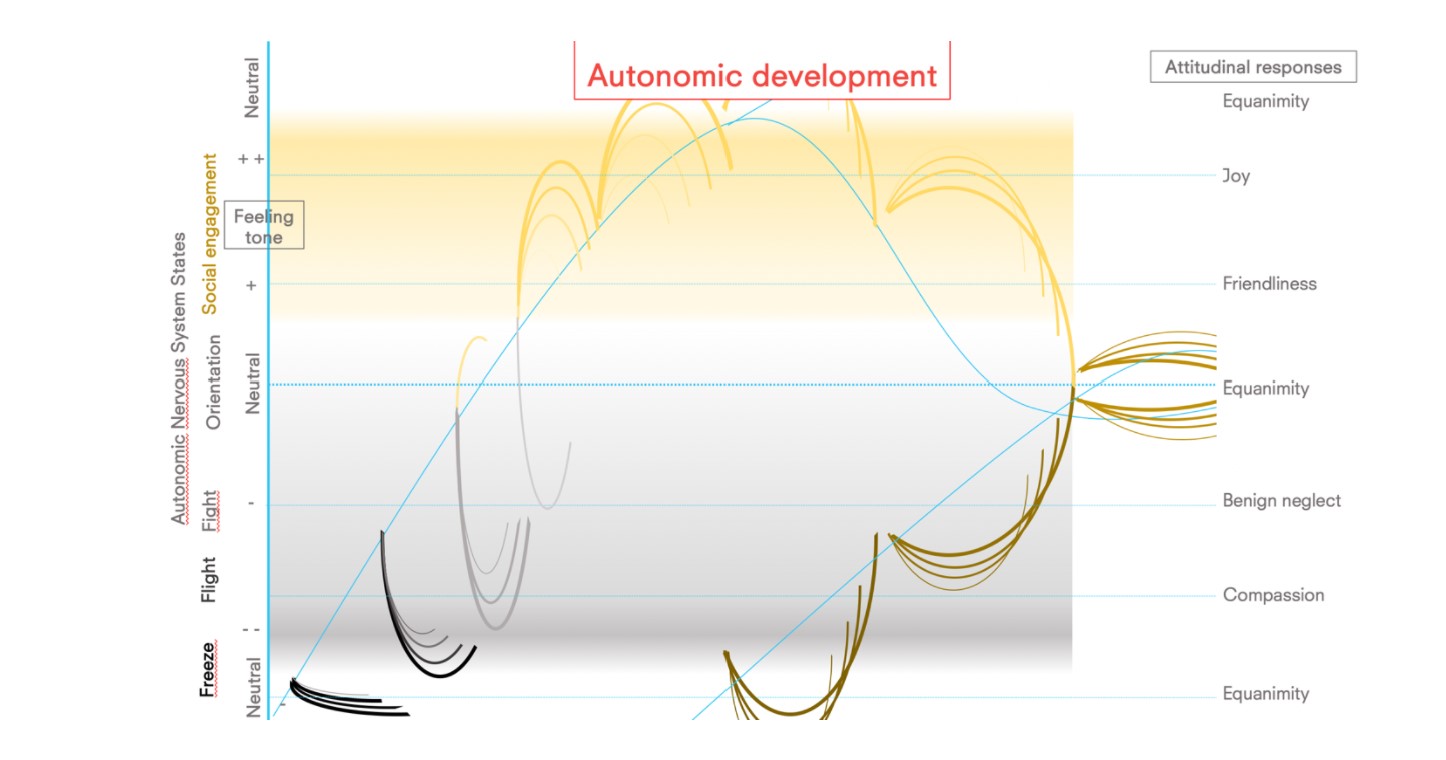

One of the most powerful tools for therapeutic success is the therapist herself. The common factors research paradigm, analyzing over 70 years of clinical data, explains that the therapeutic alliance, comprised of (i) a trusting and compassionate therapist-client relationship, (ii) clear goals and (iii) tasks to achieve these goals, is more important that any specific technique. These relational factors, common to all successful therapeutic outcomes found in the literature, can be embodied through a series therapeutic attitudes: friendliness, compassion, joy and equanimity.

In Buddhist contemplative practice these correspond to “brahma-viharas” (Hinsdale, 2012), literally meaning divine abodes. These have many similarities to Carl Roger’s (Rogers, 1986) humanistic principles of congruence, empathy and unconditional positive regard, and offer a more differentiated map based on the client’s bio-affective shifts. Simply put, a therapist would attune and respond to their clients’ bio-affective state with a therapeutic attitude that would support greater ease, often corresponding to the following pairings:

Brahma-viharic qualities

In the face of negative affect, one of the most meaningful supports a client can receive is compassion (karuna). It is a positive state of mind where one feels joy at the possibility of lending a caring hand to one in need. In some cases, when the client is in the midst of distress, it may be possible to offer an attitude of benign neglect. The therapist’s attitude of genuine friendliness (metta) creates the most basic and fundamental affective space within which the client can feel safe and develop trust. Friendliness is mostly relevant for therapists to practice when clients experience somewhat pleasant feeling tones. As a principle, as the therapeutic process evolves, therapists’ higher-level feeling tones (joy as the highest) will become attuned responses to clients’ lower-level affective tones (very negative as the lowest). Therefore, over time, it will progressively be possible to expand the quality of friendliness to neutral and negative feeling tones.

The therapeutic encounter offers many moments of joy (mudita), which is a skill where the therapist attunes to the client’s joys, even momentary upsurges of joy – feeling joy in regard to the joy of the client. As with so many causal processes in complex systems, they are bi-directional or even multi-directional. At times, therefore, it can work in the other direction: the therapist’s joy can be contagious enough to help the client rise up to that level of affective intensity. Equanimity (upekkha), synonymous with equipoise, is a balancing quality helping to bring an evenness of mind, an investigative quality to all negative and positive experiences.

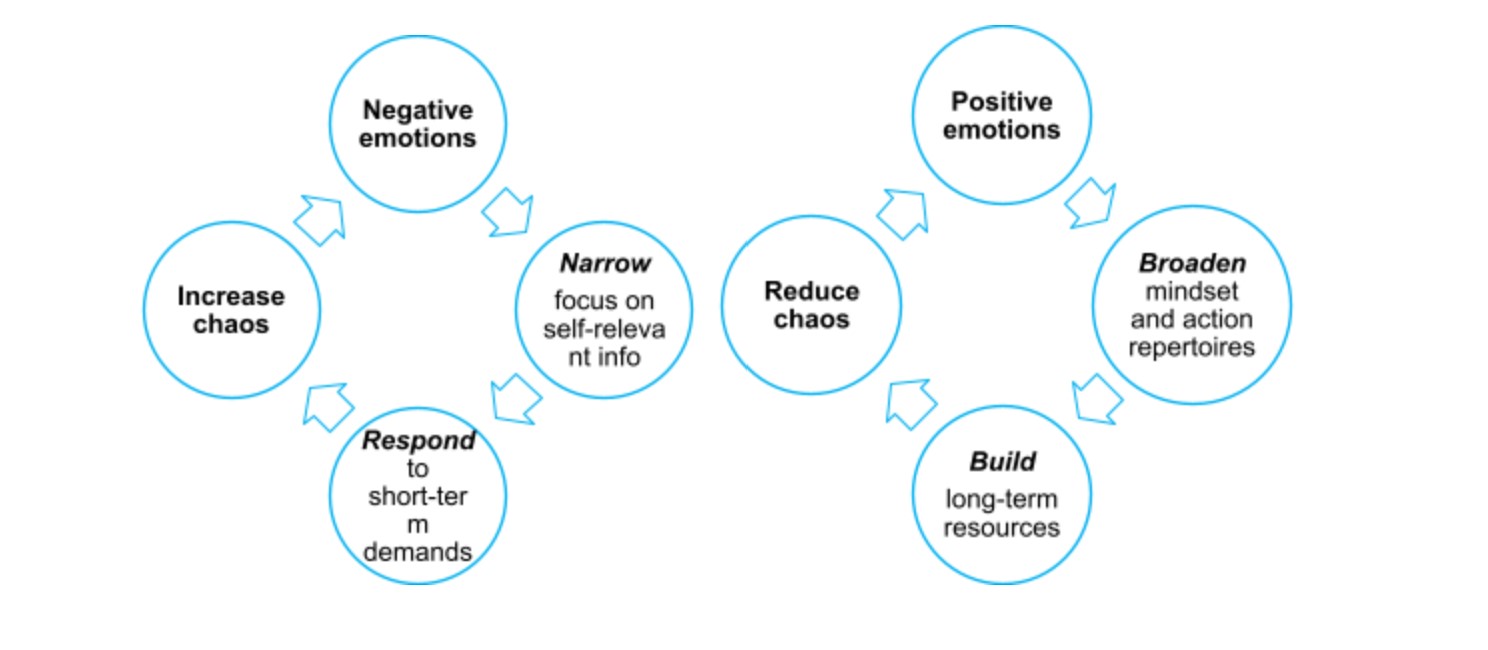

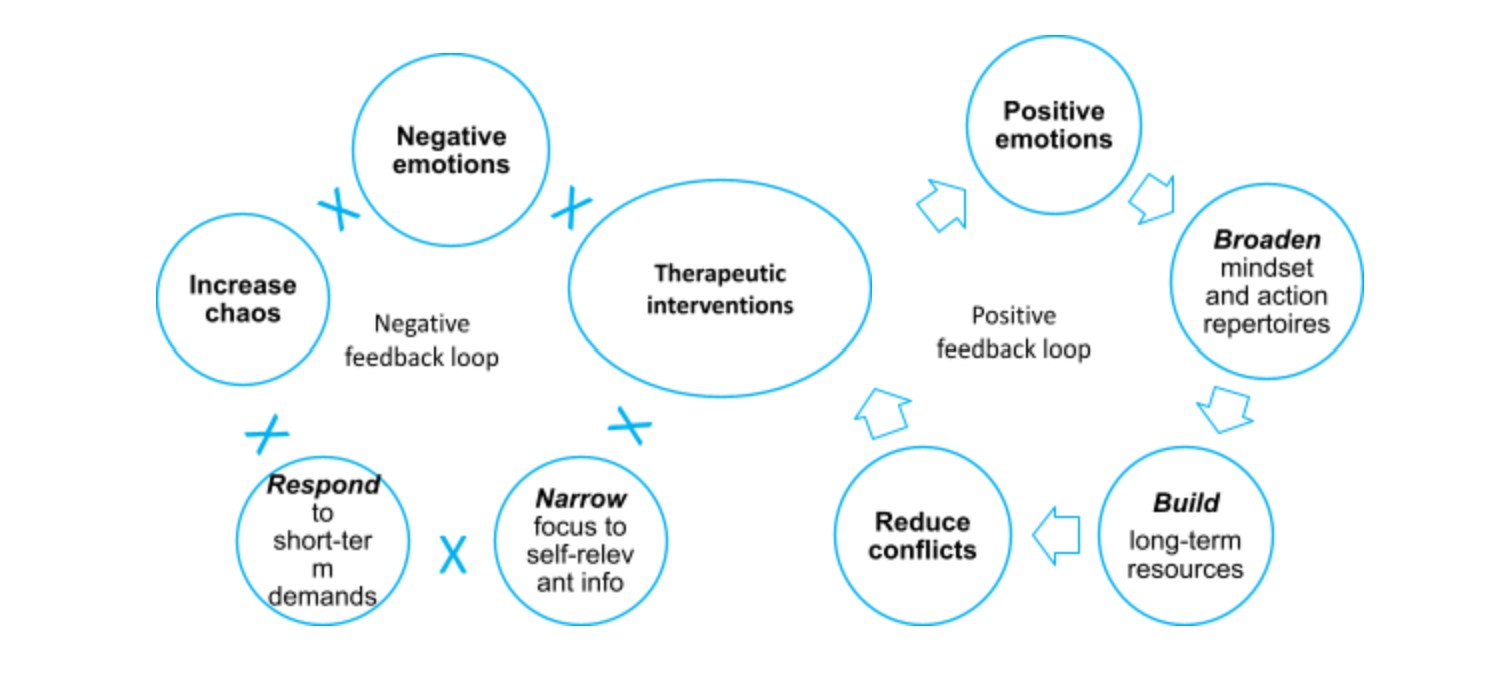

Positive emotions have shown beneficial effects in terms of their “undoing” of negativity. Fredrickson’s “undoing hypothesis” is based her empirically tested Broaden-and-Build theory (2001). The key element here is to understand the positive and negative feedback loop processes at play.

Figure 2. Positive feedback loop processes for positive & negative emotions

Experiencing positive emotions internally first help to broaden one’s cognitive and behavioural repertoires. Brain imaging studies have shown that positive emotions broaden the scope of physiological visual attention and expand people’s repertoires of openness to new experiences. At the interpersonal level, induced positive emotions increase people’s sense of “oneness” with close others and their trust in acquaintances

Benign neglect, compassion and equanimity, respectively, can be reflected as a progressive gradation of support when a client experiences difficult emotions. Friendliness, joy and equanimity, respectively, are positively reinforcing attitudes towards the clients’ progressively pleasant affective tonalities. It is initially through the therapist’s support and explicit attitudinal intervention that a client can learn to reduce their challenging states, down-regulating affective processes. By modelling an attunement and responsiveness to clients’ nervous system states, affect and socio-cognitive processes through the embodiment of brahma-viharic attitudes, clients will eventually learn to regulate their own waves, changes and movements in their bio-affective rhythms. As the client understands the importance of this attitudinal practice (clarifying this as a goal of therapy), their task is to learn to support and regulate themselves in the therapeutic setting and in their daily life.

Figure 3. Therapy-generated affective positive & negative feedback loops

In effect, positive emotions will develop a momentum via positive feedback loops of broadening and building (escalatory process), and negative emotions will be reduced both in their intensity and frequency via negative feedback loops of narrowing and responding (de-escalatory process).

A transcendent trajectory

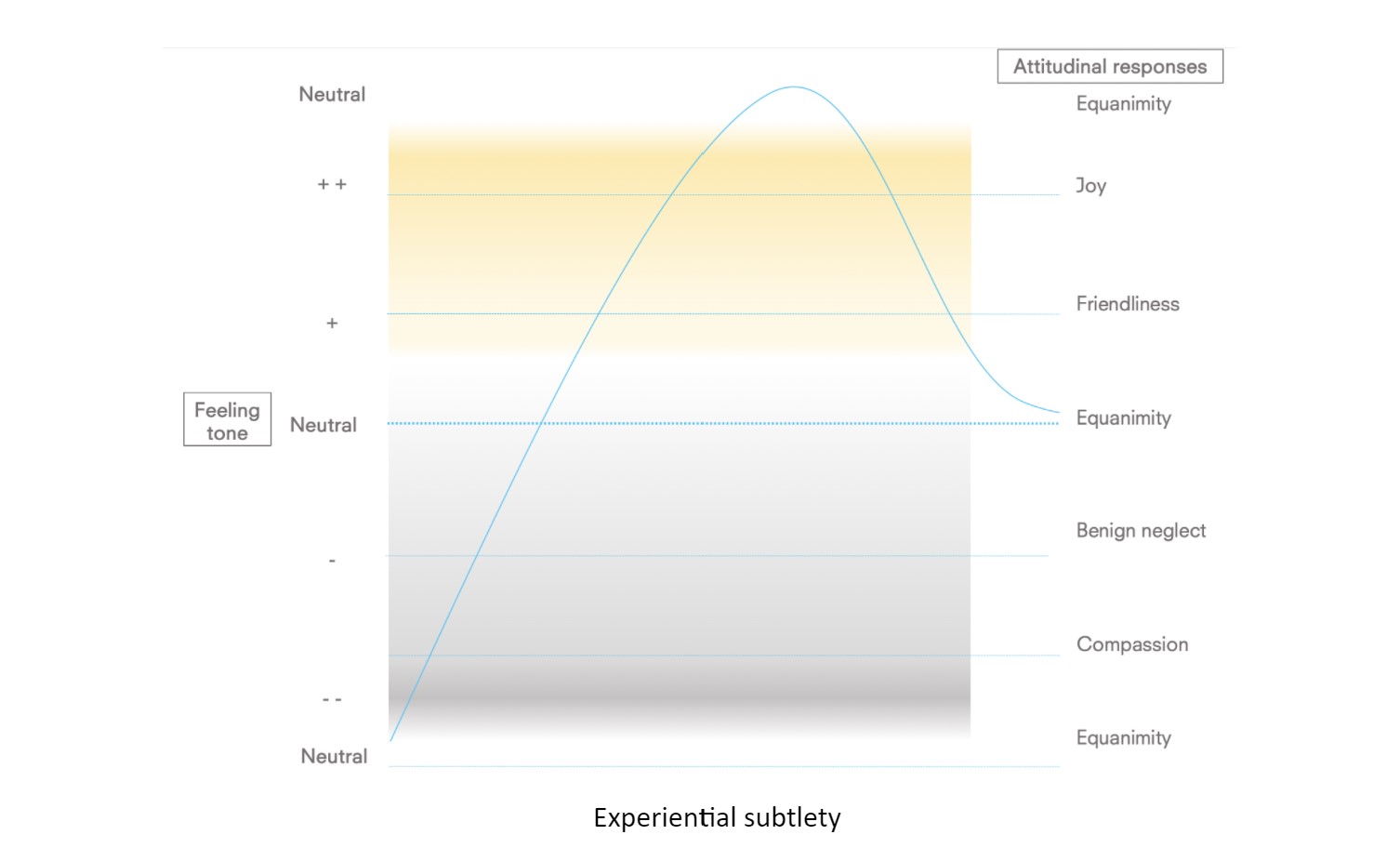

As clients begin their therapeutic journey, regulation entails a down-regulation of negative states. As the therapist, through their quality of presence, embodiment and modelling of brahma-viharic attitudes, clients are able to skillfully negotiate challenging bio-affective states, and upregulate positive states. The below diagram describes this journey as a rising curve to the highest affective tonalities, followed by a reduction in the intensity. The declining curve, indicating a reduced intensity in positive affect, is informed by Buddhist meditative maps of jhanas. These are states of increasing happiness, absorption and refined perception.

The Buddhist path to de-pathologize the psyche implies a gradual clarification, a ridding of confusion, a refinement of perception of one’s direct experience. The affective trajectory in the diagram, from left to right, describes a progressively less constructed, more subtle nature of phenomena. This means that very negative experiences are more constructed, more entangled, more fabricated than positive experiences, which are further along the process (more to the right). As affect matures and deepens, it reaches even more subtlety and stillness, taking form in equanimity, and progressively deeper states of equanimous experiences. These are experienced as higher forms of happiness the positively-valenced states preceding them, involving non-dual perception and further sensitivity to the emptiness of inherent existence of experience and phenomena.

Figure 3. Experiential subtlety

Trauma & jhana

There are important implications and correlations with this conceptual framework and that of trauma healing. Trauma occurs as a result of a nervous system overwhelm of sympathetic arousal in the autonomic nervous system (Porges & Buczynski, 2011). This leads to the nervous system to transition from sympathetic (fight and flight) to dorsal vagus (freeze) activations. A client in freeze will experience a much-reduced access to sensation, affect and orientation, and reduced sensitivity to mental images and cognitive content.

Interestingly, scientific evidence is emerging showing similarities in neurobiological substrates of jhanas and freeze states, except that these states are profoundly resourceful and transformative. They differ in three respects: (i) the preexisting conditions leading to its emergence (enjoyment training vs shock), (ii) the conceptual framework attempting to understand them (refinement of understanding the phenomenal nature of experience vs pathology) and (iii) the contiguous neurobiological networks (isolated vs interconnected) and physiological rhythms of state transition (rapid and erratic vs smooth and systematic). Freeze, a system evolutionarily designed to process backlog of sympathetic overstimulation, then, may also be a profound opportunity for cosmic connectivity and transformative meaningfulness.

The threads on the diagram, starting black and only rising, shifting through shades of grey, yellow and culminating in gold, describe the client’s progressive movement of integrated bio-affective regulation. Freeze states appear at the bottom of the graph, and clients often begin their therapeutic engagement with strong patterns of freeze, as described by the thick black threads.

Conclusion

Therapeutic presence with brahma-viharic attitudes, followed by the client’s self-organizing attunement to bio-affective states, and regulatory capacity of them, enables the process to evolve towards greater positivity (in thickening yellow threads). After reaching the peak of positivity, the system is able to experience the pendulation between approach (social engagement) and avoidance (fight-flight-freeze) states, with increasing rhythmicity and synchronicity. These wavic patterns help the process of somatic integration, leading to new levels of bio-affective agency emerging when the threshold for holding capacity of the complex interactions has been reached.

May this article be of benefit for all beings!

You can learn more about the application of these evolutionary and systemic models, their associated neuroscientific empirical research, practice and clinical interventions along with time for practice in our workshops, courses and trainings at www.neurosystemics.org.

Together we go further.

References

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American psychologist, 56(3), 218.

Hinsdale, M. J. (2012). Choosing to love. Paideusis, 20(2), 36-45.

Porges, S. W., & Buczynski, R. (2011). The polyvagal theory for treating trauma. Webinar, June, 15, 2012.

Rogers, C. R. (1986). Carl Rogers on the development of the person-centered approach. Person-Centered Review.

The purpose of therapy and coaching is to end the need for therapy or coaching. Our clients will come to see us because they need our help. In the initial stages, most of them will be dependent on us to some extent – they will re-enact their insecure/avoidant/ambivalent attachment patterns (see upcoming post for a description of attachment patterns), require some structure outside of their psychic capacity (clinical context), need to orient to a more organized bio-psychosocial system (the therapist) – and it is our duty to support them in these critical initial stages.

Our modeling of attuned humanistic attitudes and therapeutic postures of compassion, equanimity, friendliness and joy will help to reprogram the developmental mis-attunement they will have suffered throughout their life (through complex trauma, low socio-economic conditions, authoritative education, etc). Our clients’ trust in the therapeutic alliance will give us leeway to help shape:

- their internal responses to nervous system sympathetic and parasympathetic arousal and thresholds (somatics);

- their navigation of dark (negative) and lighter (positive) affective experiences (affective development);

- a higher self-esteem through self-acceptance, encouraging creative outlets, orienting them towards life-fulfilling goals and a (self-determined) ethical livelihood (cognition and self-representation), as well as;

- more securely attached relational patterns and deeper belonging in interpersonal bonds (relationships).

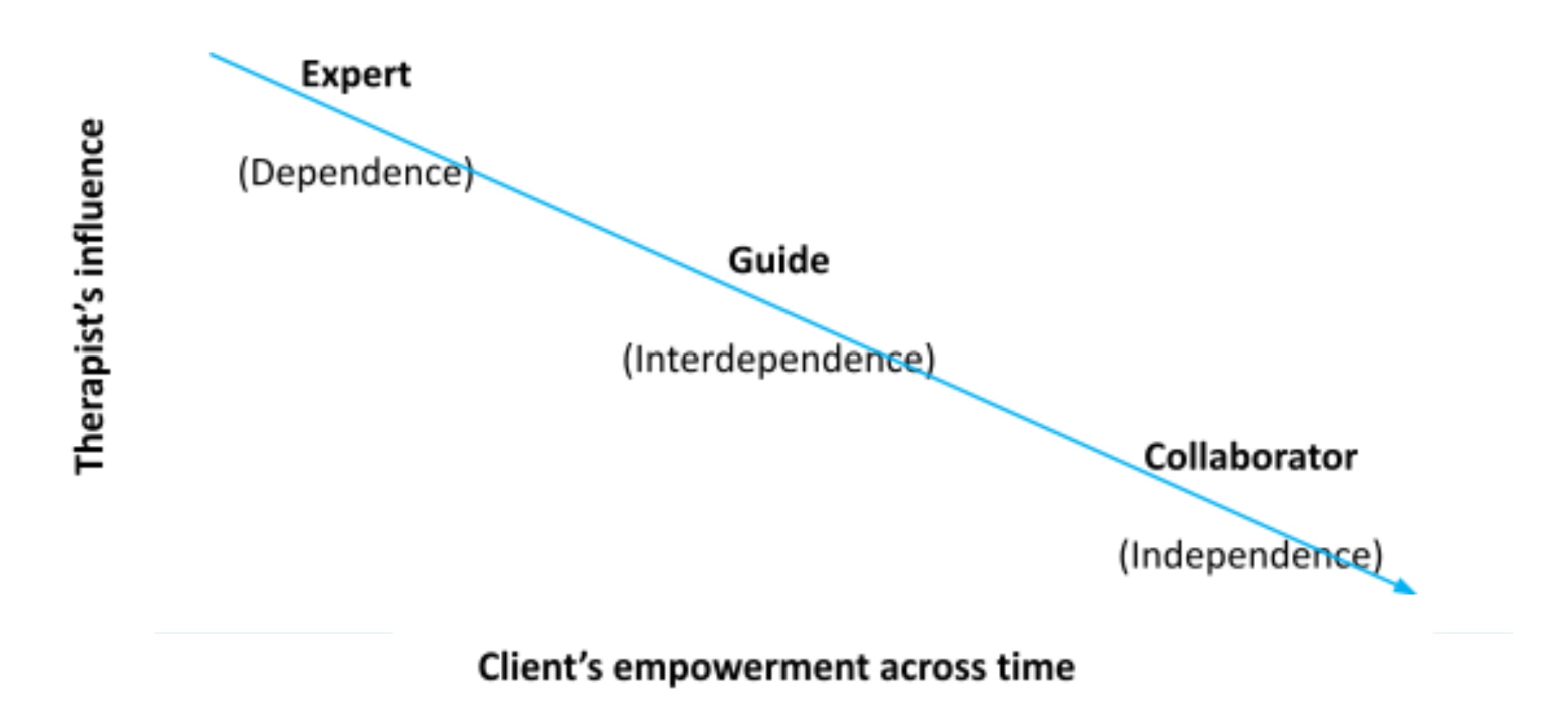

An empowering trajectory

In order to be free from therapy or coaching, our clients will need to build increasingly self-organizing capacities on all the levels described above (somatics, affect, cognition and relationships). As this empowerment process occurs, they graduate through different stages of dependency: dependence, interdependence and independence (see diagram 1).

Diagram 1. The therapists’ postures as clients integrate the empowering therapeutic experiences

Diagram 1. The therapists’ postures as clients integrate the empowering therapeutic experiences

This linear therapeutic progression initially follows a top-down structure (client dependence) to a balanced power position (therapist nourishing clients’ existing resources), to a collaborative structure (therapist bringing useful, but replaceable, spaces and inputs) in its final stage of development. As a cyclical process, the therapeutic relationship will have many implicit and explicit collaborative moments in the early dependent stages, and still some areas where the therapist will remain an expert at the ‘independence’ stage. This linear progression is only a rough schema of a complex, multifaceted and omni-relational process of development.

As the therapeutic process begins, a therapist will use their influence in various ways (i.e. attending, tuning, somatic mirroring, positive reinforcement, vulnerable self-disclosures) to feedback to the client all the external projections towards a multi-faceted empowerment (somatically, affectively, cognitively and relationally – more on this in a future blog). As the therapy unfolds, and clients integrate these empowering clinical interventions, the balance of power shifts (interdependence stage), and therapists can point more explicitly to the clients’ resources and skills, and further their organismic confidence.

At the neurobiological level, the skillful furthering and development of the client’s intrinsic organismic movements in bio-psycho-affective states gives their organism the signal “I can rely upon myself, I can count and depend on myself,” independent of the therapist’s presence or interventions. The building of self-organising capacity is one of the key factors for clients to integrate their experiences in therapy into daily life and sustain deep and meaningful transformations. As Otto Rank said, “the purpose of the therapist is to help the person to develop into that which they are” (Rank, 1936). Achieving this enables independence, ending the need for therapy. HURRAY!

May this article be for the benefit of all being.

You can learn more about the application of these evolutionary and systemic models, their associated neuroscientific empirical research, practice and interventions along with time for practice in our workshops, courses and trainings at www.neurosystemics.org.

Together we go further.

References

Rank, O. (1936). Will therapy. An analysis of the therapeutic process in terms of relationship.

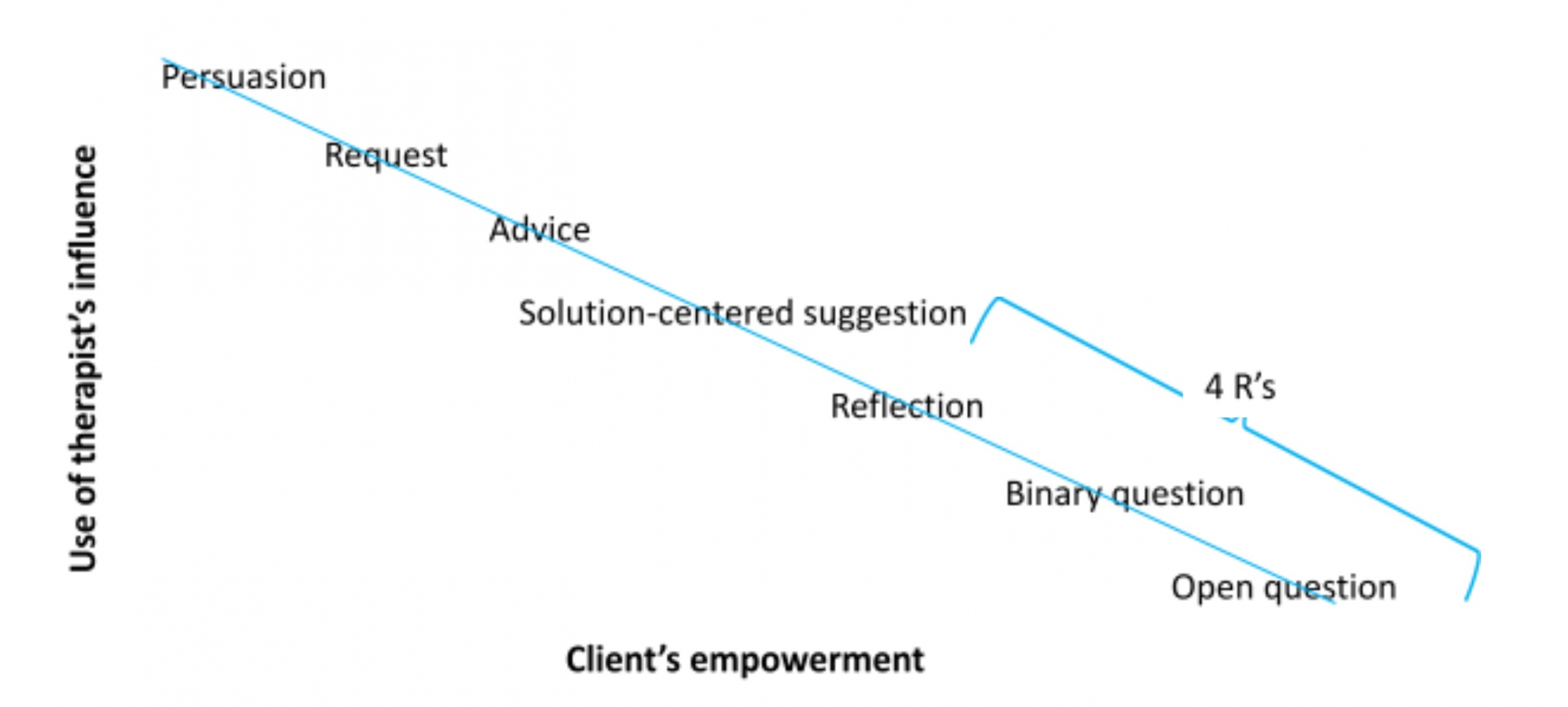

A wide-ranging review of the past 60 years of clinical practice (i.e. Baldwin, Wampold & Imel, 2007) shows that the number one factor for therapeutic success is a high-quality alliance between therapist and client, and a clarity around the goals and tasks of therapy. In this article we will provide:

- a meta-conceptual framework explaining the spectrum of therapists’ influence over the course of therapy

- specific questions, stemming from humanistic sciences (Maslow & Rogers, 1979), which help clients be more empowered, build more autonomy and trust of their own capacity

Meta-conceptual framework of clinical interventions

The initial goal of therapy is to help the therapist gain the client’s trust to build a strong alliance and raise epistemic confidence (the clients’ confidence in themselves to find their own solutions). This involves a progressive development of intimacy and trust between the therapist and client, which can be realized with the following options of therapeutic possibilities (see Diagram 1).

Diagram 1. Spectrum of therapeutic interventions as a client becomes more empowered.

Diagram 1 represents the spectrum of therapeutic interventions from more power-rich (though not power-over) to more empowering forms. This map is linear, and helpful to understand the overall journey of a client, with specific clinical interventions. However, it is important to note that as organisms, with our complex structure and non-linear cycles, we will need far more attunement and sensitivity than a simplistic formula such as this one to succeed in empowering our clients. Nevertheless, this may initially provide a helpful structure.

When a client is severely unwell, it will be helpful to provide a strong frame and use our suggestive authority to help strengthen their socio-emotional container. The interventions of persuasion (i.e. “you will need to take medication”), requests ( i.e. “please make sure you go for a walk in nature everyday”)and advice-giving (i.e. “I would recommend that you have some rest after our session”) will tend to fall in this category.

Solution oriented proposals will orient our clients strongly towards the positive, the constructive, the skilfull (i.e. “imagine you were able to achieve your goal, how would that be for you?”). It helps support a deeper sense of embodiment, confidence and belief in their agency and ability.

The 4 R’s follow: reformulate, recontextualize, review, and reinforce:

- Reformulate: using an impressionist form and tone, reflecting/mirroring back to the client what has been heard to show the therapist understands what they have shared and helps build/restore the therapist-client collaboration and dance. Reformulations also help structure the narrative and/or present emotion, key points can be amplified, emphasize the posture of curiosity and not-knowing, the therapist can also make helping additions and use different wordings to broaden the discourse, while checking the client shares these developments. In most reformulations, there is the formulation of a relatively complex hypothesis relevant to the client. These are sub-categories of reformulation:

- Simple repetition (parrot): reflect back word-for-word what the client shared, as precisely as possible (usually for high arousal disclosures).

- Verification: verifying the meaning of certain sentences, feelings, descriptions

- Simple reflections: neutral reformulation

- Double reflections: repeating two often contradictory points of view or experiences to underline ambivalence (refrain from using “but”)

- Recontextualise: help bring greater precision and specificity to the client’s situation (difficulty or ease). Asking for examples or situations that are space and time bound enables a crossover from a more conceptual, verbalized cognitive generality to an embedded and embodied experience. This promotes a re-centering of attention on the experiential qualities of the discourse/narrative and allows give opportunities for the client to feel recognized and understood by the therapist. Here are some examples:

- “Could you give me a recent example of what you are describing?”

- “When was the last time this occurred?”

- “How does this manifest in your daily life?”

- Review/Recap: summarise the client’s sharings to make sure they have been understood. They can occur at any time and may be very brief (2-3 sentences) or quite in-depth (a few minutes). Recapping helps the client feel understood and build a common vision and therapeutic alliance. They can be particularly useful at the end of a session to start slowing down and reducing new input into the session, as well as revisiting some of the key themes and moments of the session. The client participation can also be encouraged by asking them to review the session(s) themselves, saying for example:

- “What have been the key learnings/takeaways/experiences from this session?”

- “What do you make of all of this?”

- “In one word, how would you sum today’s exchange together?”

- Reinforce: positive reinforcement is part of a shaping and conditioning paradigm which aims at increasing the level of confidence in certain pattern, thereby raising the probability of that skillful behaviour to arise again. It is a powerful tool initially to strengthen the therapeutic alliance, and then supports the client’s feeling of self-efficacy. They offer important spaces for satisfaction, appreciation and celebration in the midst of the client recounting challenging situations. One can reinforce:

- Facts: underline a client’s action or behaviour in the past or in the present, which they have done or refrained from doing.

- People: emphasize the helpful qualities present as the client is sharing.

- Affect: recognizing suffering, normalizing it and offering encouragement and compassion (i.e. “in this situation, it is normal to feel…”)

May this article be for the benefit of all beings.

You can learn more about the application of these evolutionary and systemic models, their associated neuroscientific empirical research, practice and interventions along with time for practice in our workshops, courses and trainings at www.neurosystemics.org.

Together we go further.

References

Baldwin, S. A., Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2007). Untangling the alliance-outcome correlation: Exploring the relative importance of therapist and patient variability in the alliance. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 75(6), 842.

Maslow, A. H., & Rogers, C. (1979). Humanistic psychology. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 19(3), 13-26.

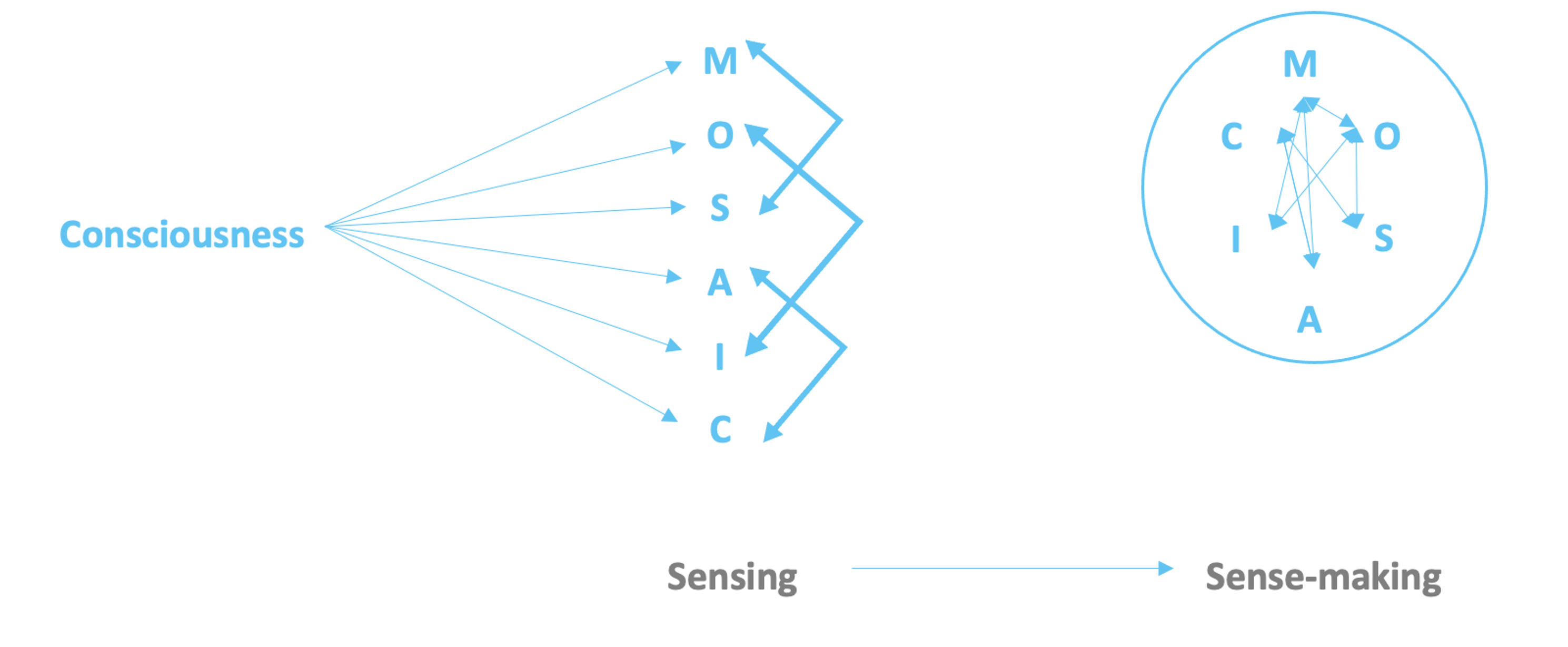

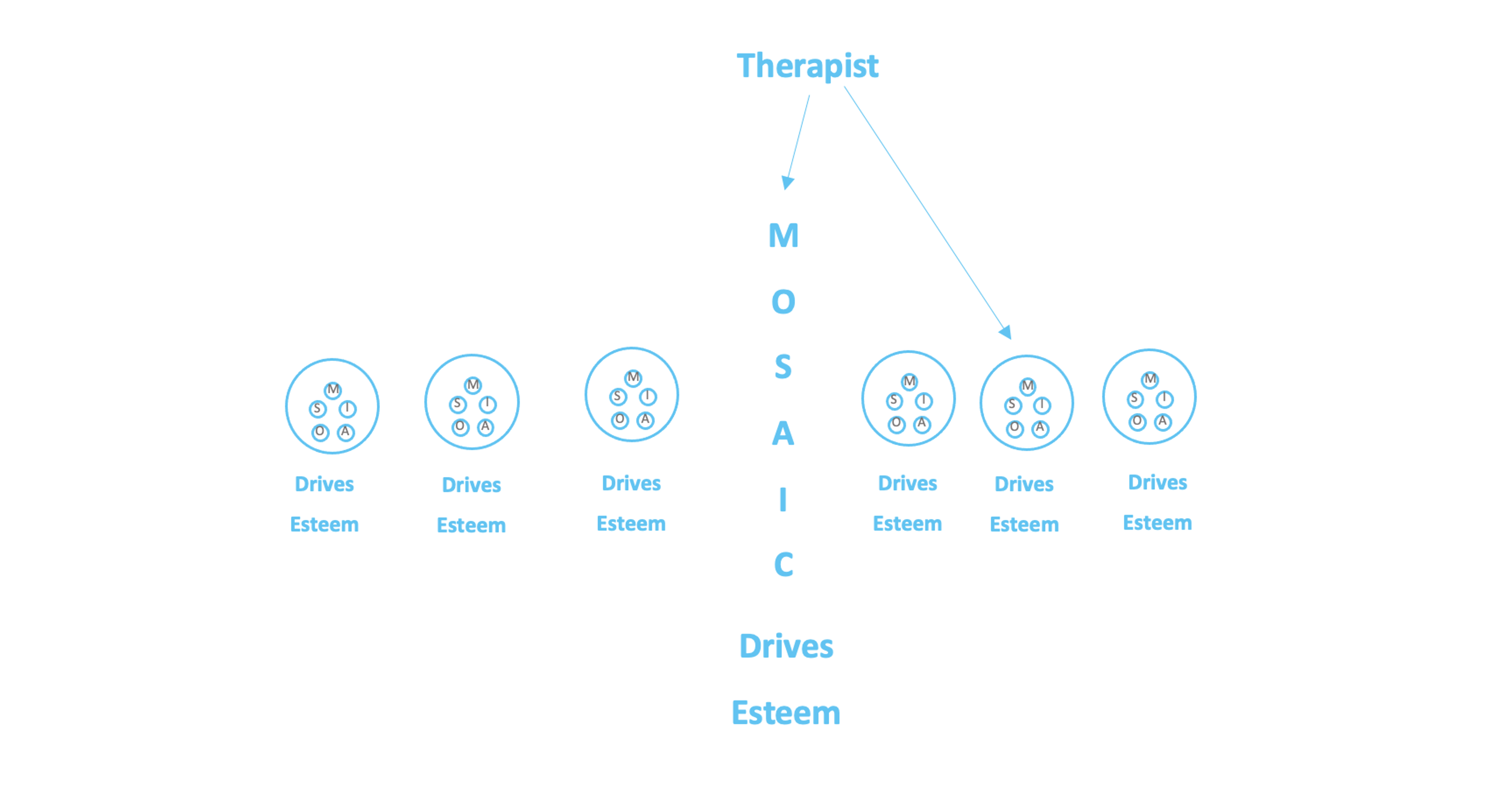

One of the most important benefits of a group is co-regulation, and the good news it that our brains are neurally wired for it. Regulation is the ability to skillfully balance and assume volitional capacity on a particular system (i.e. attention, breathing, emotions, cognition and/or a group of people). In NeuroSystemics we have a gradual, step-by -step and “holonistic” approach to co-regulation, which can be understood in 3 steps: (i) sensing into and embodying the fullness of one’s immediate experience through all possible channels, (ii) strengthening and rooting a solid sense of self-esteem and goal-oriented directionality and choicefulness in individuals and (iii) inquiring into each of the participants’ experience in the group, and containing the complexity and diversity of resonance to allow a coherent sense of wholeness to emerge. Let us describe each of these stages in more detail.

(i) Sensing into and embodying the fullness of one’s immediate experience through all possible channels

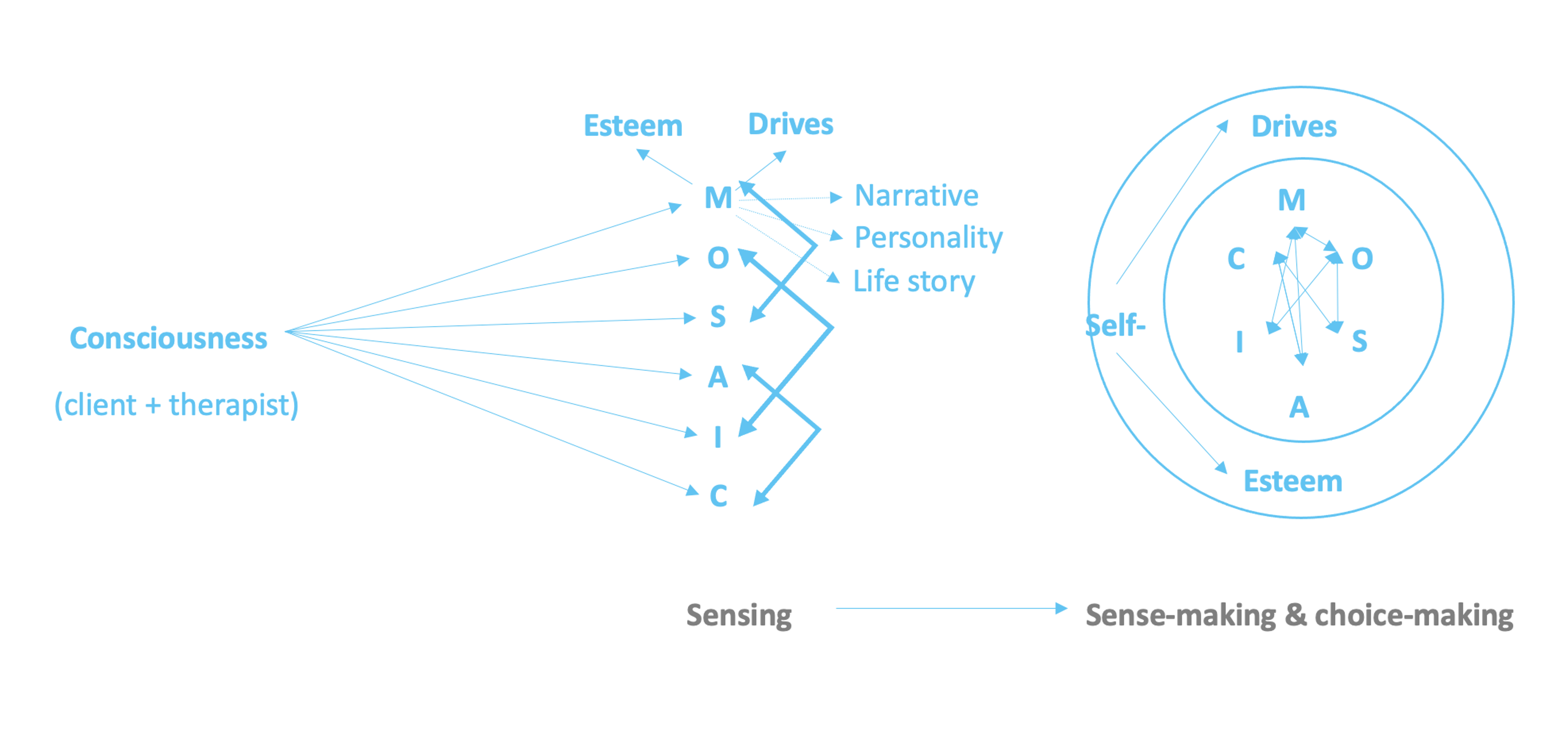

In NeuroSystemics, we consider the content of one’s present moment experience to be subdivided in 6 possible ways, understood in the acronym MOSAIC:

- Meaning: Narrative, personality & biography

- Orientation: Present moment sensing of the environment

- Sensation: perception of physiology

- Affect: Feeling tones, emotions & moods

- Image: Mental images & imaginal constructs

- Consciousness: Knowing faculty of the mind

The main regulatory agent in this first stage in our clients’ consciousness, their capacity for kindly awareness and compassionate mindfulness. As our clients, in their own intra-psychic ways, are able to sense into their different channels and cultivate nervous system bandwidth to sustain attention in each of them, increased connectivity between each of the channels occur. Our clients go from sensing to sense-making:

(ii) Strengthening and rooting a solid sense of self-esteem and goal-oriented directionality & choicefulness in individuals

As our clients build more networks between the MOSAIC channels of their immediate experience, feel more embodied and oriented to the here-and-now, it’s possible to engage in a deeper exploration of the ‘meaning’ channel by investigating our individual clients’ narratives, personality and life-stories they have and need to share. This enables a robust sense of self-esteem and self-drives. As our clients make more sense of their immediate embodied experience, they are then able to make clearer choices in their lives. Collectively with the MOSAIC networks of our clients’ immediate experience, these psycho-biological processes function as a springboard to enter a group setting.

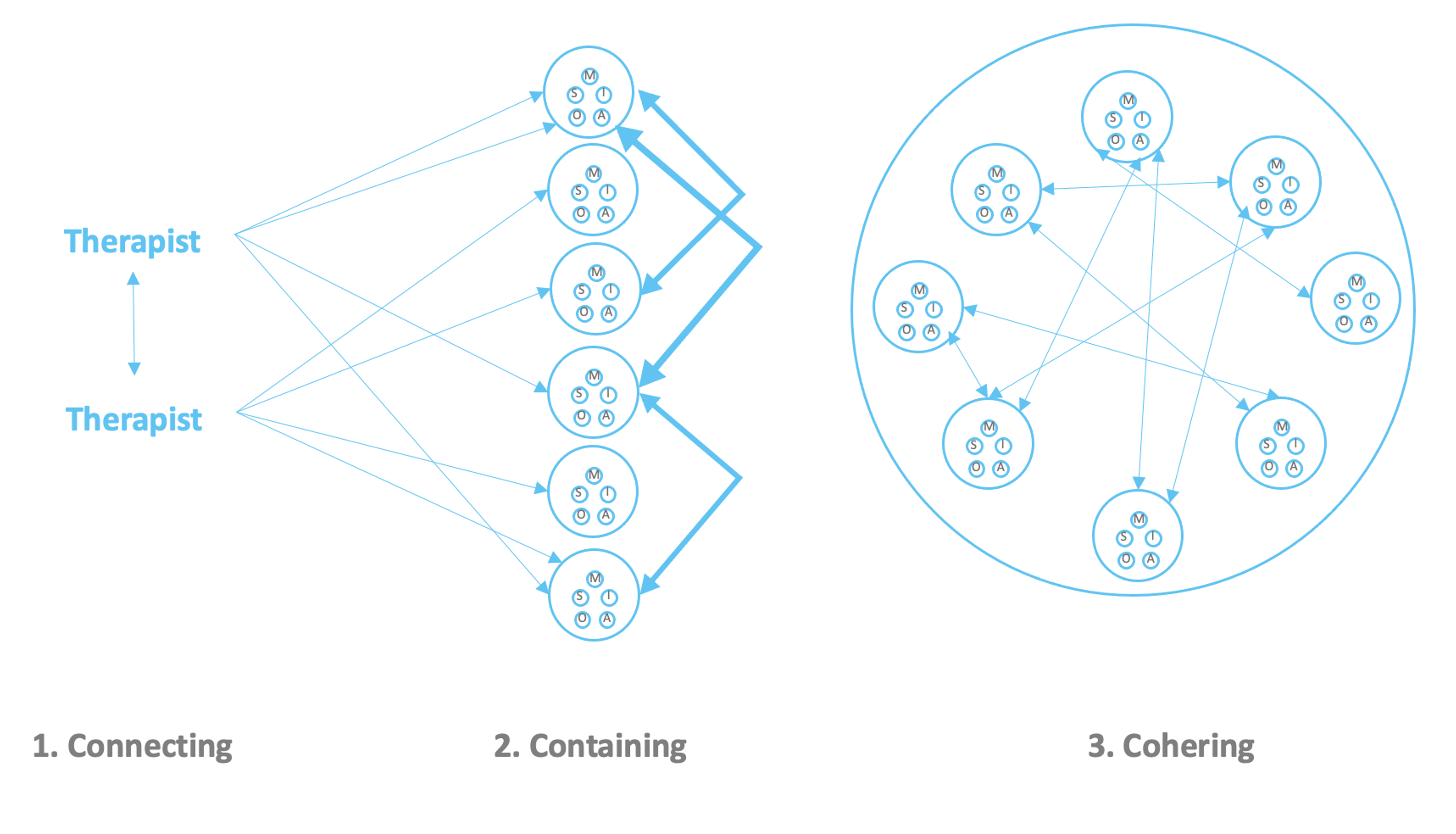

(iii) Inquiring into each of the participants’ experience in the group, and containing the complexity and diversity of resonance to allow a coherent sense of wholeness to emerge.

In the same way that an individual breathes in and breathes out, groups, as social organisms, breathe in when attention is given to the whole group (horizontal inquiry) and breathes out when focus is given to one individual in particular (vertical inquiry). Each individuals’ MOSAIC is then supported to network within its own channels, as well as co-networking with other individuals through the therapist’s active linking between them:

Therapists go through a 3-step process to help

- individuals in the group differentiate themselves, their MOSAICs, archetypic forms of self-esteem and idiosyncratic drives

- facilitate intergroup communications in order to contain the growing complexity of views, opinions, backgrounds, feelings, sensate experiences

- enable coherent moments emerging to be valued and embodied in individuals and the group-as-a-whole.

According to Porges & Buczynski (2011), feeling safe in groups activates a number of brain networks, including:

- The limbic system supported through acceptance, nonjudgment and empathy

- Neo-cortical circuitry, enabling memory reprocessing and restructuring, leading to the formation of more secure attachment patterns.

Group therapy can provide the safe and accepting environment that allows dissociated implicit memories to be held in kindness long enough to receive the disconfirming experience that is offered by the group’s growing capacity to resonate with and meet distressed individual members (Siegel, 2018). In this way, the group members learn to co-regulate one another and function as a unified whole, a social organism.

In NeuroSystemics, therefore, we link between intra-personal integration at the individual level (vertical inquiry) to inter-personal integration (horizontal inquiry). This dialectic between vertical and horizontal mechanics enable an omni-directional process of integration to enable group members to be fully oneself while embedded in the oneness of the group. By connecting to participants, containing interactions and cohering emergent insights and experiences in a paced, gentle and inviting progression, neural wholeness emerges.

May this article be for the benefit of all being.

You can learn more about the application of these evolutionary and systemic models, their associated neuroscientific empirical research, practice and interventions along with time for practice in our workshops, courses and trainings at www.neurosystemics.org/event-calendar.

References

Porges, S. W., & Buczynski, R. (2011). The polyvagal theory for treating trauma. Webinar, June, 15, 2012.

Siegel, D., (2018) in Badenoch, B., & Gantt, S. P. (Eds.). (2018). The interpersonal neurobiology of group psychotherapy and group process. Routledge.

There is emerging consensus in the field of psychotherapy that relationships matter more than techniques. Over 60 years of empirical data of clinical practice, insights in quantum physics, contemplative and complexity sciences all back this up. How can we make sense of these findings and adapt our clinical interventions accordingly to harness the breadth of potential therein to increase nervous system resiliency, an empowered sense of self and interpersonal connection and belonging? NeuroSystemics was conceived precisely for this purpose.

One of the key contributions of NeuroSystemics to the field of clinical practice is to provide a meta-model which incorporates maps and tools for increasingly complex practice settings: (i) mental skills, (ii) 1:1 sessions and (iii) group therapy. A number of systemic principles can be applied to each of these practice settings, and the quality of relationship is one of those essential factors. The relational stance fractally reiterates itself in self-similar expressions in each of these settings and needs to be facilitated accordingly. A brief description of how relational qualities can be nourished to support a successful therapeutic outcome will now be given.

1. Mental skills: relating to experience & within experience

Since the earl 20th century, science has experienced a radical paradigmatic transition from linear to non-linear dynamics. Einstein’s special theory of relativity, followed by Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle and Gödel’s incompleteness theorems, have shaken our Newtonian understanding of reality as a solid and objective experience. These recent insights start to account for the impact of the observer, the experimenter, consciousness itself.

Contemplative sciences, emerging from the most subtle meditative inquiry into the nature of reality, provide a similar conceptual framework whereby any and all experience are fundamentally empty of inherent existence. They arise as a result of causes and conditions, imbedded in infinite interdependent networks of matter and mind. Consciousness is one of these conditions which contribute to the arising of experience on a moment-to-moment level. Therefore, the quality of consciousness, that is, the way in which one’s direct experience is apprehended, the way consciousness relates to the object of experience, significantly influences the way the experience manifests.

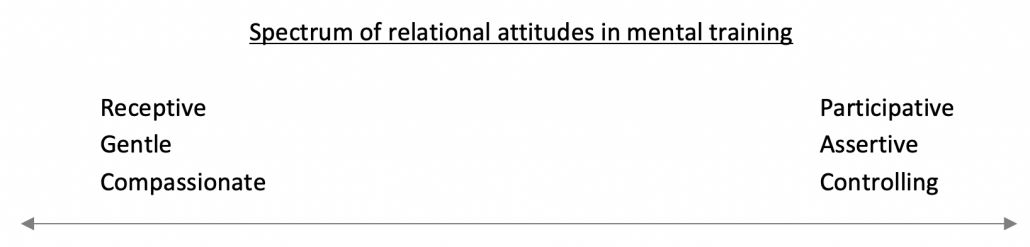

As an initial practice of mental training, NeuroSystemics thereby brings a lot of emphasis to cultivating a whole spectrum of skillful qualities of mind such as receptive, gentle compassionate on one end (colloquially understood ‘being’), and more participative, assertive and controlling attitudes (colloquially understood ‘doing’). Being controlling is often understood as a problematic stance and something we should strive to let go of. However, upon careful examination of our intrapsychic experience, it will become clear that there are moments when we feel overwhelmed, and it simply is not possible (and therefore not desirable) to attempt maintaining receptivity. Since no experience has inherent existence, the fundamental skill to learn is adaptiveness, not a reified mental attitude. This concords with Darwin’s understanding of fitness and adaptiveness as being our most essential forms of intelligence. This means that we should build skills on the whole spectrum of relational dispositions, and engage with our experience adaptively to provide the best possible regulatory and emancipatory outcome.

Once the appropriate attentional relationship to experience is achieved, further mental skills can be developed to progressively weave associative networks between the different dynamics of our experience. For example, we help to form interdependent links between different sensations in the body (shifting from local to more global physiological awareness), between the body and feelings, extending further to include cognitive processes and content.

Evolution can be defined as increasing orderly complexity. When training consciousness, it is possible to further this developmental trajectory by complexifying the associations between stimuli, to reach infinitely inclusive state of mind. These highly coherent and organizing states strengthen resiliency, upregulate positive affect and build durable well-being. This is where a previously overwhelming experience, such as trauma, can be transformed into a movement of post-traumatic growth.

In sum, NeuroSystemics encourages the strengthening of relational qualities to experiences, starting with the attitude of consciousness itself. It gently supports more complex interdependent patterns weaving each arising contents of experience (sensations, feeling, cognitions) into an integrative systemic web and reinforcing attentional stay-power and resiliency.

2. 1:1 Sessions: relating to the client & their daily life

Clinical practice has enjoyed over 60 years of empirical research. We are now able to discern some of the most important psychotherapeutic success factors. The common factors’ research paradigm, based on rigorous statistical analyses, emphasizes the importance of the relationship between the therapist and the client more so even than the therapeutic technique. This means that one of the main active ingredients to engage in at first, is to build a sense of trust and appreciation between the therapeutic environment. Rogers’ humanistic triad of empathy, unconditional positive regard and congruence are essential to actualize this potential.

Secondly, as a therapeutic contract, the common factors’ approach encourages the setting of clear goals and tasks to achieve these goals. This fosters a co-creative and participative dynamic within the client, seeking to strengthen and empower the clients’ intrinsic self-organisational impulses. This is key because, aside from the relational qualities between therapist and client, the other array of success factors pertain to extra-therapeutic dynamics. The clients’ activities and environment have great influence on their building of resiliency and healing.

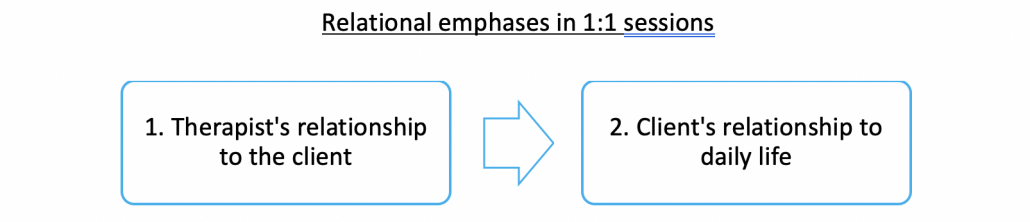

Relational emphases in 1:1 sessions

As a consequence, NeuroSystemics emphasizes not only the trusting and compassionate therapist-client relationship, but also the relations that the client can make between experiences in therapy. As much emphasis is given to therapeutic experiences as to the client’s transferential assimilation of these into their daily life and relationships outside of therapy. Therapeutic considerations therefore extend much beyond the clinical hour, and webs of interdependent associations are weaved and integrated.

Group therapy: multi-directional relationships

Neurophysiological research has provided key insights to. appreciate the power of being in safe, trusting and enjoyable relationships. Cohen and Sbarra’s social baseline theory demonstrates the ways in which friendly social connection is perceived as a bioenergetic resource, reducing the quantity of effort required to accomplish tasks if friends were not present. Through fMRI research combining neuroanatomic and social psychology they found that the proximity of friends reduces neuroaffective, neurocognitive and neuromotor energy expenditures. This means it is easier to regulate emotions and behaviour in the presence of good company. By forming a rigorous alliance with clients, therapists can help reduce the required nervous system capacity to access the freeze states and release the stored charge in a gentle, safe and even enjoyable fashion.

Also, Porges’ polyvagal theory explains the ways in which a nourishing social contact will, to an inversely proportionate degree, reduce an individual’s tendency to experience states of fight, flight and freeze.

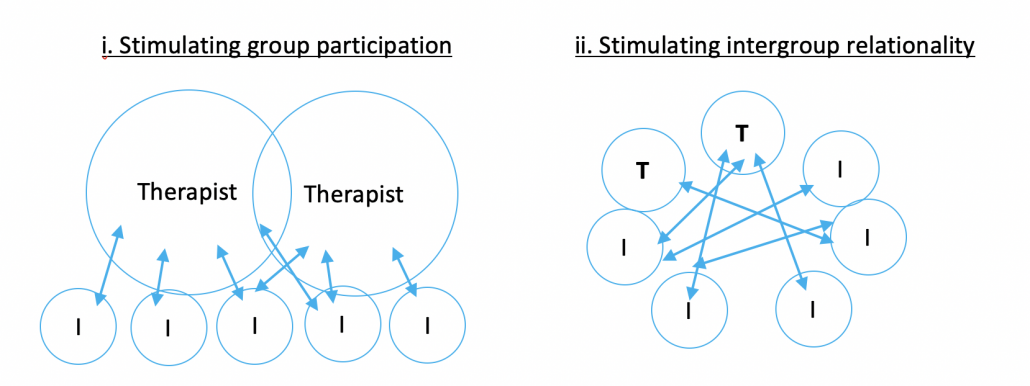

As a consequence, it is of prime importance to build a strong alliance (as described in 1:1 sessions above) and support clients’ participation and engaging socially. Initially, therapists will (i) stimulate individual participation and as safety grows, (ii) exchanges will occur directly between group members. The web of relationships grows to build a net of connections which begins to replace the role of therapists in holding the group safety and development. This second stage maximizes participation, intimacy and social embeddedness. It also fosters a more democratic and non-hierarchical distribution of power and influence in the group.

Conclusion: Integrating a multi-dimensional perspective

NeuroSystemics provides a multi-dimensional framework to harness the power of relationships in mental training, 1:1 sessions and group therapy. Quantum and contemplative sciences describe the malleability of experience through the qualities of perceptual consciousness. Mental training therefore involves the cultivation of a whole spectrum of relational attitudes in order to best adapt to emerging experiences. Practically, this may mean relating to one’s experience with assertiveness when sensing the possibility of overwhelm, and applying greater receptivity when there is greater balance.

In 1:1 sessions, the therapist will journey with their clients to co-create relational safety. This offers possibilities to deepen the clients’ own capacity and skills to embody and integrate therapeutic experiences into their daily life. This 2-step relational development has shown to account for over 70% of the variance for psychotherapeutic success, and NeuroSystemics 1:1 sessions have been conceived based on this structure.

Group processes provide a rich context of practice to build on our evolutionary momentum to increase orderly complexity. Whether through the individual inquiry, active empathy and step-by-step building of trust, or through the receptive empathy and facilitating direct interactions between members, relationality is has center focus in this context of praxis. In the same way. that the physiological organism breathes in and out, the oscillation between these two forms of relational engagements offer unique emergent possibilities of both belonging and individuation.